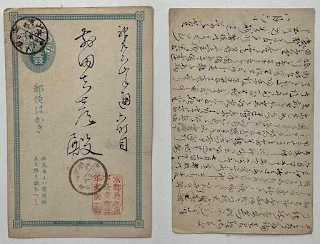

Although some correspondence of Hirase Yoichiro is preserved in the Smithsonian Collection, these letters are limited to the period between 1900 and 1923. Additionally, a few letters are found in the collection of John Read le Brockton Tomlin (see 2 photos of typewritten letters from their collection below), a prominent British malacologist, but these also date from the later years of Hirase's life. To date, no correspondence from his earlier years has been discovered outside of our collection, which includes six postal cards spanning 1889 to 1891: January 2, 1889; March 25, 1889; August 6, 1889; January 1, 1890; July 9, 1891; and August 5, 1891. These early correspondence provide valuable insights into Hirase's formative years as a malacologist and naturalist.

All six cards bear a postmark from 山城京都 (Yamashiro Kyōto). Four of them feature Hirase Yōichirō's personal red stamp, which includes his name and address: 平瀬與一郎, 京都烏丸通, 下長者町北 (Hirase Yōichirō, Kyōto Karasumaru-dōri, Shimochōja-machi Kita). Notably, Hirase occasionally uses the simplified character "与" instead of "與" when handwriting his name, appearing as 平瀬与一郎.

Hirase Yoichiro (平瀬 與一郎, 1859–1925) was a pioneering Japanese malacologist, naturalist, and renowned researcher specializing in shellfish. His groundbreaking contributions to the field of malacology earned him widespread recognition. Following in his footsteps, his son, Hirase Shintarō (平瀬 信太郎, 1884–1939), also became a distinguished malacologist, further solidifying the Hirase family's legacy in the study of mollusks. Hirase made substantial contributions to the understanding of Japanese shellfish during the Meiji and Taisho periods. His research was entirely self-funded, which eventually led to financial and physical exhaustion, preventing him from fully realizing his dream of cataloging all Japanese shellfish. Despite these challenges, Hirase's work laid the foundational knowledge for future Japanese malacologists.

Hirase dedicated much of his life to the study of mollusks, amassing an extensive collection of shells and identifying over 700 new species. His meticulous research significantly advanced malacology in Japan, a field that had previously been dominated by Western scholars. Recognizing the need for a platform to disseminate knowledge, he founded Kai Ryū Zasshi (Conchological Magazine) in 1907, Japan's first periodical dedicated to the study of mollusks. This publication not only facilitated scientific discourse but also encouraged Japanese researchers to contribute to the growing body of knowledge on marine life.

In 1913, Hirase established the Hirase Conchological Museum in Kyoto, which housed his vast collection and served as a hub for research and education. His dedication to collecting and classifying mollusks provided future generations with a wealth of knowledge and an invaluable resource for continued study. However, unlike many of his contemporaries who relied on institutional backing, Hirase funded his research entirely on his own. This placed an immense financial strain on him, as he covered the costs of expeditions, specimen preservation, and publication expenses out of pocket.

Artistic Contributions

While Hirase was a scientist at heart, his appreciation for the aesthetic beauty of shells was equally profound. His most notable artistic endeavor was Kaigara Dammen Zuan (貝殻断面図案), published in 1913. This woodblock-printed book showcased intricate cross-sectional designs of shells, revealing their natural symmetry and structure in a way that was both scientifically accurate and artistically compelling. The book, produced by the renowned Kyoto publisher Unsōdō, reflects a harmonious blend of traditional Japanese printmaking techniques and modern scientific illustration.

Hirase’s work in Shell Motifs highlights his ability to transform natural forms into mesmerizing artistic compositions. His renderings of shell interiors, with their delicate spirals and layered formations, resemble abstract art while maintaining their scientific integrity. The precision and elegance of these depictions suggest that Hirase viewed mollusks not only as subjects of study but also as objects of beauty. His artistic vision extended beyond mere documentation—he sought to capture the inherent patterns and complexity of marine life in a way that would inspire both scientists and artists alike.

Personal Sacrifices and Legacy

Despite his passion and dedication, Hirase’s self-funded research eventually took a toll on him. The financial burden of maintaining his collection, producing publications, and sustaining his museum led to significant hardship. As his resources dwindled, his ability to continue his work diminished. Coupled with the physical exhaustion of fieldwork and meticulous study, these challenges ultimately prevented him from fully realizing his dream of cataloging all Japanese shellfish. His museum, once a center for malacological research, eventually closed, and much of his collection was dispersed.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment