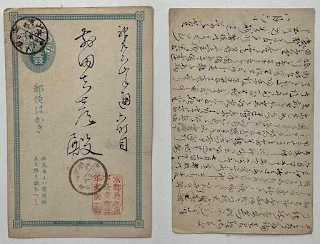

Postmarked on March 20, 1891—though the date is partially obscured, we believe the year is correct based on other cards in this collection—this rare and unusual postal card was sent from Yamashiro, Kyoto, to Maeda Yoshihiko, a Western-style painter in Kobe. The message appears to express gratitude to Maeda for hosting the sender and their companions in Kobe. It also lists five prominent artists who attended the gathering. Given that Hikita’s name appears on the far left and we have another message written by him for comparison (see below), we are certain that Hikita was the author of this note.

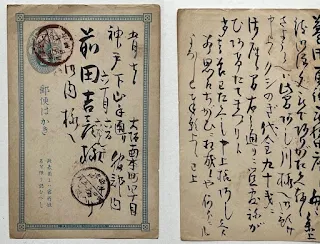

Another card, dated May 22, 1891, from Yamashiro, Kyoto, features two senders: Hikita Keizō (疋田敬蔵) and Yamashita Kumata (山下久馬太). Yamashita, a lesser-known artist, is primarily recognized for his 1887 painting of the Garyū Pine, titled 臥竜松真写: 臥竜松在于備前和気郡大内村一ノ井氏庭中 (True Depiction of the Garyū Pine: The Garyū Pine Located in the Garden of the Ichii Family in Ōuchi Village, Wake District, Bizen). Beyond this work, Yamashita’s artistic influence is further evidenced by his role as a drawing instructor for Kojima Torajirō (児島虎次郎, 1881–1929), highlighting his involvement in the artistic community of the Meiji era.

The Meiji period (1868–1912) was a transformative era in Japanese history, marked by rapid modernization and the adoption of Western ideas and techniques. This cultural shift extended to the arts, where a group of visionary artists embraced Western-style painting, blending it with traditional Japanese aesthetics to create a new artistic identity. Among these trailblazers were Ōhira Hiromasa, Tamura Sōryū, Morizumi Isana, Koyama Sanzō, and Hikita Keizō. Each of these artists not only mastered Western techniques but also dedicated their lives to teaching and promoting this new art form, leaving an indelible mark on Japan’s artistic landscape.

Ōhira Hiromasa (大平廣正) : The Educator and Advocate

Ōhira Hiromasa (1858–1901) was a pioneering Western-style painter and art educator from Fukui Prefecture. After graduating from middle school, he began his career as an art teacher, but his passion for Western painting led him to Tokyo, where he studied under Honda Kinkichirō at the Shōgidō art school. Ōhira played a crucial role in the early Western-style art movement in Japan, co-founding the Meiji Art Society (Meiji Bijutsukai), the country’s first Western painting organization. His dedication to art education was evident in his teaching roles at institutions like Fukui Middle School and Fukui Girls' High School, where he nurtured the next generation of artists. Today, his works are preserved in the Fukui Prefectural Museum of Art, serving as a testament to his contributions to the evolution of Western-style art in Japan.

Tamura Sōryū (田村宗立): The Monk Who Bridged East and West

Tamura Sōryū (1846–1918), a Buddhist monk and artist, was instrumental in introducing Western-style painting to Kyoto. Born in Tanba Province, Tamura displayed artistic talent from a young age, studying traditional Nanga painting before transitioning to Western techniques. His fascination with realism led him to acquire a camera and study oil painting under European mentors, including British artist Charles Wirgman. Tamura’s influence extended beyond his own works; he taught at the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting and later established the Meiji Art Institute, where he mentored emerging artists. His self-portrait, housed at the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto, exemplifies his mastery of Western realism. Tamura’s ability to blend Western techniques with traditional Japanese themes made him a pivotal figure in the evolution of modern Japanese painting.

Morizumi Isana (守住勇魚): The Innovator of Kyoto’s Art Scene

Morizumi Isana (1854–1927) was a key figure in introducing Western-style art to Japan. Born in Tokushima Prefecture, Isana began his artistic training under his father, a Sumiyoshi school painter, before moving to Tokyo to study Western techniques under Kunisawa Shinkurō and Italian painter Antonio Fontanesi. Isana co-founded the Jūichi-jikai (Eleven Members Society) to promote Western-style painting and later moved to Kyoto, where he taught at Doshisha University and the Kyoto Higher School of Art and Craft. His contributions to Kyoto’s textile industry, particularly his designs for Nishijin textiles, showcased his versatility. Isana’s works, such as "Male Nude" and "Landscape," are preserved at the Tokyo University of the Arts Museum, reflecting his enduring influence on Japan’s art scene. Morizumi Chikana (守住周魚), younger sister of Isana, was also a painter.

Koyama Sanzō (小山三造): The Lithographer and Exhibitor

Koyama Sanzō (1860–1927) was another prominent Western-style painter of the Meiji era. Born in Shizuoka Prefecture, Sanzō studied at the Kobu Art School in Tokyo before relocating to Kyoto, where he became a professor at the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting. After resigning in 1881, he ventured into lithography, producing art reproductions and instructional materials. Sanzō was an active participant in the art community, organizing exhibitions with fellow artists like Morizumi Isana and Tamura Sōryū. His later years were spent in Fushimi, Kyoto, where he continued to innovate and contribute to the artistic dialogue of his time.

Hikita Keizō (疋田敬蔵): The Botanical Illustrator

Hikita Keizō (1851–?) was a Western-style painter and educator who studied under Antonio Fontanesi at the Kobu Bijutsu Gakko. In 1879, he founded the Meiji Art School to promote Western-style painting and later joined the Hokkaido Development Commission, where he showcased his talent with works like "Autumn Scenery of the Ishikari River." Hikita’s dedication to art education was evident in his teaching role at the Kyoto Prefectural Art School. After retiring, he focused on lithography, compiling his botanical illustrations into the "Keiran Gafu," a collection that remains a testament to his artistic vision and contribution to art literature.

A Collective Legacy

Together, Ōhira Hiromasa, Tamura Sōryū, Morizumi Isana, Koyama Sanzō, and Hikita Keizō represent the vanguard of Western-style painting in Meiji Japan. Their individual journeys—marked by a relentless pursuit of knowledge, a commitment to education, and a passion for innovation—collectively shaped the trajectory of Japanese art. By blending Western techniques with Japanese sensibilities, they created a unique artistic language that continues to inspire and influence artists today. Their legacy is not only preserved in their works but also in the countless students they mentored and the institutions they helped establish, ensuring that their contributions to Japan’s artistic heritage endure for generations to come.

.jpg)