This card is postmarked in 摂津大阪 (Settsu Osaka) on December 11, 1891, and is written in pencil. The return address is listed as 大阪久宝寺 (Osaka Kyūhōji), likely referring to a temple in the area. The sender’s name appears to be 糸谷表 (Itotani Omote or Itoya Hyō), though the reading is uncertain. From what we can decipher, the message follows the typical format of many postal cards from this period, featuring generic exchanges of thanks, greetings, and wishes for good health. Despite efforts to find more information, no significant details about 糸谷表 have surfaced in online searches.

Maeda Yoshihiko (前田吉彦, 1849–1904), also known by his artistic name Gizen (蟻禅), was a Japanese Western-style painter of the Meiji period, though he remains largely unknown outside Japan. This blog presents previously unpublished insights into his life and work through correspondence from historical figures and fellow artists of the time, offering a unique glimpse into his personal connections and the cultural context of the era.

Friday, February 28, 2025

Thursday, February 27, 2025

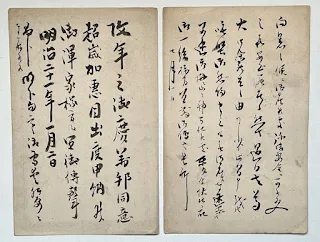

Two Unreadable Postal Cards from 1889 Osaka

The names and messages on these cards are unreadable to us. Both cards are postmarked in Settsu, Osaka (摂津大坂), with dates of June 22, 1889, and February 17, 1889.

The February card is particularly interesting because it shows red ink postmark impressions on the reverse side in mirror image. This suggests that the cards were stacked with some weight on them, causing the ink from another card’s postmark to transfer onto the back of this one.

Nakanoshima Osaka 1889 and 1890 Greeting Cards

Both of these cards are simple New Year’s greetings sent to Maeda Yoshihiko by someone named Kenichi (研一). The sender’s full name includes an undecipherable surname, written as X藤 (X Fuji), making it difficult to identify him further. The cards were sent from Nakanoshima, Osaka (大坂中之島), with postmarks from Settsu Osaka (摂津大坂) and dated January 1, 1890, and January 2, 1889. Unfortunately, the inability to fully decipher the sender’s surname limits our ability to conduct further research into his identity or his connection to Maeda Yoshihiko.

Wednesday, February 26, 2025

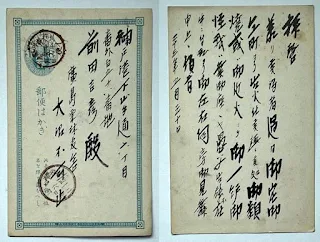

Mino-Owari Major Earthquake of October 28, 1891

This postal card, postmarked in Osaka and dated October 31, 1891, was sent by Nakajima Takejiro (中島武郎) to Maeda Yoshihiko in Kobe. In an earlier post (see October 2, 2024), we featured another card from Nakajima, titled "1888年 芸術学生中島武郎から師匠 前田吉彦宛の年賀状" ("New Year's Greeting from Art Student Nakajima Takejiro to Master Maeda Yoshihiko"), which bore a Tokyo postmark. Once again, we encounter the intriguing term 六要堂 (Rokuyōdō) on this card.

As we’ve discussed in previous posts, 六要堂 likely refers to an art class, studio, or cultural space associated with Maeda Yoshihiko, possibly involving a small group of individuals. Its repeated appearance in these cards suggests that it played a central role in the artistic or educational activities of Maeda and his circle during the Meiji period.

We have yet to identify who Nakajima was, but the fact that both cards address Maeda as sensei (teacher) strongly suggests he was once Maeda’s student. A personal touch appears on this postcard, where Nakajima wrote on the address side: 10月/ 30日 / ヨル (night of October 30). Why would he include that detail?

This 1891 postal card is interesting, as Nakajima inquires Maeda'a welfare and whether he was affected by the recent earthquake. From the date, he must have referring to the Mino-Owari Earthquake of October 28, 1891.

The Mino-Owari Earthquake of October 28, 1891, was one of the most powerful earthquakes in Japan’s recorded history, with an estimated magnitude of 8.0. The epicenter was in the Nōbi Plain, affecting present-day Gifu and Aichi Prefectures. The quake caused widespread destruction, toppling buildings, collapsing bridges, and triggering landslides. The famous Neodani Fault, which runs through the region, experienced a massive surface rupture extending over 80 kilometers, with vertical and horizontal displacements exceeding six meters in some areas. More than 7,000 people lost their lives, and tens of thousands of homes were destroyed. The disaster was one of the first in Japan to be extensively documented with photographs, contributing to the early study of seismology.

The earthquake's impact was not limited to the immediate area; tremors were felt as far away as Tokyo and Kyushu. The damage prompted discussions on improving building techniques, as many traditional wooden homes collapsed under the intense shaking. The event also influenced Japan’s emerging scientific community, leading to advancements in earthquake research. Reports of the disaster spread quickly through newspapers, and letters such as the one you have provide insight into how people in distant cities, like Kobe, reacted with concern. This earthquake remains a significant historical event, marking a turning point in Japan’s understanding of seismic activity and disaster preparedness.

Sunday, February 23, 2025

陸軍中尉 山口長成

Postmarked January 11, 1892, from Kobe, this New Year's greeting card was sent to Maeda Yoshihiko by Yamaguchi Nagatari or Nagashige (山口長成). From what we can decipher of the message, he appears to mention military service. We believe he retired as an Army First Lieutenant in 1884. While we found a photograph of him online, we have no further information about him or his service record.

Thursday, February 20, 2025

1886 神戸の油画師 前田吉彦

These two cards were postmarked in Osaka, one on January 2, 1888, and the other on July 2, 1886. Both were sent by 仲小路体亮 (Nakashōji Tairyō?), who listed his address as 大坂府西成郡 (Nishinari-gun, Osaka). The connection between him and Maeda Yoshihiko remains unclear. The 1888 card contains only a customary New Year’s greeting, offering little insight. However, the 1886 card is more intriguing. In it, Nakashōji refers to Maeda with the title 油画師 (aburashi – oil painting artist) and expresses gratitude for a message Maeda had sent about an urgent matter. Unfortunately, the specifics of this matter may forever remain a mystery.

Friday, February 14, 2025

備中 六要堂 前田吉彦

These three postal cards, sent on January 1, 1890, December 6, 1891 (by Miyake?三宅), and December 23, 1891 (by Suzuki?鈴木[?]津郎) , originate from Bitchu (備中) and bear postmarks from 吹屋 (Fukiya), 笠岡 (Kasaoka), and 成羽 (Nariwa). Two of the cards include a return address from 川上郡 (Kawakami-gun), which is part of present-day Takahashi City (高梁市), Okayama Prefecture. This region holds particular significance as the birthplace of Maeda Yoshihiko, the recipient of these cards.

One of the cards January 1, 1890, sent by an individual named 幾田収 (Ikuta Osamu), features the intriguing term 六要堂 (Rokuyōdō) in the address. As we’ve explored in previous posts, 六要堂 likely refers to an art class or studio, possibly run by Maeda Yoshihiko himself, perhaps in collaboration with a few other individuals.

Whether it was a formal studio, a gathering place for artists, or a small class, 六要堂 appears to have been a significant location for creative or intellectual exchange during this period. If you have any insights or additional information about 六要堂 or the individuals associated with it, we would love to hear from you!

Unfortunately, we have no further information about the senders of these cards. The messages appear to be customary greetings, with the January 1 card likely being a New Year’s greeting. The other cards, sent in December, may have been seasonal greetings or personal updates, reflecting the social customs of the time.

Tuesday, February 11, 2025

Maeda Yoshihiko and 六要堂 of Kobe

This postcard, postmarked in 播磨姫路 (Himeji, Harima) on January 4, 1891, was sent by 島村賢三郎 (Shimamura Kenzaburō), who lists his address as 姫路市龍野町二丁目 (2-chome, Tatsuno-cho, Himeji-shi). Shimamura addresses the recipient as 前田吉彦先生 (Maeda Yoshihiko-sensei) and includes the unusual term 六要堂 (Rokuyōdō) alongside his name.

So far, we have seen Maeda referred to with titles such as 洋画師 (yōgashi), 油画師 (abura-e-shi), 油絵師 (abura-e-shi), 六要画 (rokuyōga), and 油画先生 (aburaga-sensei). However, this is the first instance of the term 六要堂 (Rokuyōdō). Its meaning remains unclear, as the term does not appear in standard Japanese language references. It may refer to something like the "House of Rokuyō" or a place associated with Maeda's work, such as an art studio or school. It is possible that Shimamura was once a student of Maeda.

In this letter, Shimamura informs Maeda of his upcoming military service, noting that he will be unable to correspond for some time. He also expresses deep gratitude for Maeda's past kindness and mentorship. Despite our efforts, we have been unable to uncover additional information about Shimamura Kenzaburō, leaving his story and connection to Maeda a tantalizing mystery.

Sunday, February 9, 2025

Bitchū Jitō Postmarked Cards (備中地頭)

These three postal cards, dated September 1, 1889, January 1, 1890, and July 30, 1891, bear the postmark of 備中地頭 (Bitchū Jitō). One of the cards includes a return address from 備中川上郡 (Bitchū Kawakami-gun), a region that historically covered parts of what is now Takahashi City (高梁市)—the birthplace of Maeda Yoshihiko. This connection suggests that the senders may have had personal or regional ties to Maeda, though the exact nature of their relationship remains unclear.

One appears to read 三宅美津太郎 (worked in agriculture?), and the other 三宅?郎 (三宅美津太郎's father/relative?). The third card has a postmark over the name making it unreadable.

As we continue to explore these cards, we hope to uncover more about the senders and their connections to Maeda Yoshihiko. Each card is a small but valuable piece of history, offering clues about the social and cultural practices of the Meiji period. If you have any insights or additional information about these individuals or the region, we would love to hear from you!

Saturday, February 8, 2025

Three Bizen Okayama Postmarked Cards 1889 and 1890

All three of these postal cards bear the postmark of 備前岡山 (Bizen, Okayama) and are dated October 7, 1889, January 1, 1890, and August 1, 1890. Among the senders, one name stands out clearly thanks to a distinct square red ink stamp, which we believe reads 松原全五郎 (Matsubara Zengorō). Unfortunately, despite this clear identification, no historical records have been found to shed light on who Matsubara Zengorō was or his connection to the recipient.

Another sender’s name appears to be 足立一 (Adachi Hajime), though this interpretation is less certain due to the handwriting. Like Matsubara, Adachi’s identity remains a mystery, and no additional information about him has been uncovered. All the senders are from Okayama-shi, suggesting a possible local network of correspondents or a shared community tied to Maeda Yoshihiko of Takahashi, Okayama.

Friday, February 7, 2025

広島市大手町九丁目と前田吉彦の関係

What was the connection between 9-chome, Ōte-machi, Hiroshima, and Yoshihiko Maeda? This question becomes even more intriguing as we examine two additional postal cards sent to Maeda. One card was sent by 大谷健一 (Ōtani Kenichi) on January 1, 1890, and the other by 堤正巳 (Tsutsumi Masami) on January 5, 1890. Both cards were postmarked in 安芸広島 (Aki Hiroshima), and both senders listed their return address as 広島市大手町九丁目 (9-chome, Ōte-machi, Hiroshima).

The address 9-chome, Ōte-machi appears frequently in historical records, including the 文部省職員録 大正5年11月1日調 (Ministry of Education Staff Directory, compiled on November 1, 1916) and other related directories from Hiroshima during that period. However, these records typically include Banchi (番地), or street numbers, which were essential for accurate mail delivery. This raises an interesting question: why do these cards omit the street numbers?

Banchi referred to specific districts within cities, often covering large areas. Without precise street numbers, delivering mail accurately would have been challenging unless the individuals were well-known in their neighborhood. This suggests that Ōtani Kenichi and Tsutsumi Masami might have been prominent figures in 9-chome, Ōte-machi, or that the address itself was widely recognized, possibly housing a government office, school, or other institution.

Wednesday, February 5, 2025

Unknown Historical Figures of 安芸広島 Aki Hiroshima

These four postal cards all bear the postmark of 安芸広島 (Aki Hiroshima). Two of the cards are dated January 2, 1889, while the others are marked February 8, 1890, and May 31, 1890. The senders’ names are listed as 大沼不可止 (Ōnuma Fukashi), 大沢省三?(Ōsawa Shōzō), 片山桂三? (Katayama Keizō), and 門山 (Kadoyama). Despite effort, no historical records have been found for these individuals, leaving their identities and connections shrouded in mystery.

Monday, February 3, 2025

高井半九 Hiroshima Ōte-machi 9 Chōme

These two postal cards were sent from 安芸広島 (Aki Hiroshima) by 高井半九 (Takai Hankyu) of 広島市大手町九丁目 (9 Chōme, Ōte-machi, Hiroshima-shi). The cards are dated January 5, 1890, and May 29, 1890. Takai Hankyu appears to have been a government employee in Hiroshima, as his name is listed in the "Hiroshima Prefectural Staff Directory" from February 1889 and other official government records. This discovery leads us to believe that 9 Chōme may have housed government offices during that time, adding an intriguing layer of historical context to these correspondences.

While sending New Year's cards has long been a cherished tradition in Japan, we were surprised to learn that sending cards in May was also a common practice in the Meiji era. May marks the transition from spring to summer, a season celebrated for its pleasant weather, blooming flowers, and vibrant natural beauty. Sending cards during this time may have been a way to share seasonal greetings and updates.

As we continue to explore these historical postal cards, we hope to uncover more about the lives of individuals like Takai Hankyu and the role of 9 Chōme, Ōte-machi in Hiroshima’s history.

Sunday, February 2, 2025

Maeda Yoshihiko 油画師 Sensei - 広島市

These five postal cards bear the postmark 安芸広島 (Aki Hiroshima) and are dated August 17, 1889, January 3, 1890, June 18, 1890, June 24, 1891, and September 2, 1891. The sender, whose identity remains unknown, lists their return address simply as 広島市 (Hiroshima-shi)—at least, that is the only portion we can decipher with certainty.

The sender addresses Maeda Yoshihiko as 先生 (sensei), a term of respect often used for teachers, mentors, or individuals of high status. This suggests that the sender may have been a former pupil. Adding to the intrigue, on two of the cards, Maeda is referred to as 油画師 (Aburaeshi), meaning "oil painter." This title provides a fascinating clue about Maeda’s profession or artistic pursuits during this period.

These cards offer a captivating glimpse into the relationship between the sender and Maeda Yoshihiko, as well as the cultural and social practices of the Meiji era. The use of formal titles like "sensei" and "Aburaeshi" highlights the respect and admiration the sender had for Maeda, while the variety of dates suggests an ongoing correspondence that spanned several years.

There is a strong possibility that the sender of these cards may have been a public servant in Hiroshima, potentially working at 広島市大手町九丁目 (9 Chōme, Ōte-machi, Hiroshima-shi). While we cannot say this with absolute certainty, the evidence from other Hiroshima-postmarked cards in this collection makes this idea quite plausible. Many of the cards sent to Maeda Yoshihiko from this address appear to have originated from individuals associated with local government or public service, suggesting that 9 Chōme may have been a hub for government offices or related activities during the Meiji era.

Unsolved Mystery of Hiroshima Ōte-machi 9 Chōme

We have four postal cards here, all sent from 安芸広島 (Aki, Hiroshima) and dated January 6, 1888, May 24, 1889, January 1, 1890, and May 31, 1890. While we are unable to fully decipher the texts, they appear to contain customary greetings and well wishes, typical of correspondence from that era.

The sender is identified as 桑戸学 (Kuwato Manabu), who listed his return address as 広島市大手町九丁目 (9 Chōme, Ōte-machi, Hiroshima-shi). This address is particularly intriguing to us, as several other individuals also sent cards to Maeda Yoshihiko from the same location, as we will explore in upcoming posts.

What was this address? Was it a residence, a school, a business, or something else entirely? The passage of time, especially the upheaval of World War II, has erased much of the historical context. The 9 Chōme no longer exists today, having been replaced by 5 Chōme in the postwar reorganization of Hiroshima.

Saturday, February 1, 2025

明治美術會 為田鍛 1892

Here are three postcards sent from 播磨明石 (Akashi, Harima), now part of Hyogo Prefecture. They are postmarked January 2, 1889, March 14, 1889, and May 29, 1890, and were sent by 為田鍛 (Tameda Kaji?). His return address is listed as 明石町大明石村 (Oakashi-mura, Akashi-cho).

Tameji seems to have been connected to the Meiji Art Association, as his name appears in their 1892 publication, 明治美術會報告 第16回 (Meiji Bijutsu Kai Hokoku, 16th Report). He was also likely an educator at the Hyogo Prefectural Agricultural College, as his name is mentioned in the Hyogo Prefecture Education Bulletin from 1886 to 1889 (兵庫県教育雑報 第85-95号).