渡辺文三郎 (薇山) 明治22年東京五姓田塾からのはがき

The discovery of this postal card, along with other cards written by Watanabe Bunzaburō that will be introduced in time, is nothing short of remarkable. Sent to Maeda Yoshihiko and remaining unseen for 135 years, they offer invaluable insight into a crucial period of Western-style painting.

This card bears a postmark from 下谷東京 (Shitaya, Tokyo), an area near present-day Ueno Park and close to Asakusa, where Goseda Hōryū's art class was located. Sent on May 29, 1889, Bunzaburō listed his address as #68 Naka-Okachimachi, Shitaya, Tokyo. It appears he ran out of space, writing his name as 渡辺文三, omitting the 郎.

Just a few weeks earlier on May 1, 1889, Watanabe Bunzaburô, along with Goseda Yoshimatsu (五姓田義松), Yamamoto Housui (山本芳翠), Goseda Hōryū (五姓田芳柳), Goseda Hōryū II (五姓田芳柳 二代目), Watanabe Yūkō (渡辺幽香), and three dozen other artists attended the inaugural meeting of the Meiji Art Society.

Watanabe Bunzaburō (渡辺文三郎, 1853–1936), also known as Bizan, played a pivotal role in the development of Western-style painting in Japan during the Meiji period. Born in Kanagawa Prefecture, Bunzaburō initially studied traditional Japanese art before moving to Tokyo in 1873. At that time, Japan was undergoing rapid modernization, and Western artistic influences were beginning to shape the country's cultural landscape. Like many of his contemporaries, Bunzaburō became drawn to the Western techniques that were making their way into Japan, marking a shift in his artistic journey.

In Tokyo, he joined Goseda Hōryū’s art school, Goseda Juku (五姓田塾), where he learned to blend Western techniques with traditional Japanese themes. Goseda, who had studied under British artist Charles Wirgman in Yokohama, was one of the early pioneers of Western-style painting in Japan. His school focused on the Yokohama-e style, which depicted Japan’s landscapes and people with a realistic approach, often for export purposes. Under Goseda’s mentorship, Bunzaburō was exposed to oil painting and perspective, which played a significant role in his artistic evolution.

Bunzaburō’s life took a significant turn in 1876 when he married Yūkō (幽香), the daughter of Goseda Hōryū. Yūkō was a talented artist in her own right, known for her delicate depictions of nature, especially flowers and portraits. Though her work was rooted in traditional Japanese aesthetics, it also reflected the influence of Western styles, bridging the two worlds in a way that was characteristic of the era. Her contributions to the Western-style painting movement were significant, and her collaboration with Bunzaburō further solidified their role in the broader artistic shift of the time.

The couple’s partnership had a lasting impact on Bunzaburō’s work, and Yūkō’s influence helped him gain prominence in the art world. Their shared passion for art and mutual support led to a fruitful artistic environment, one that played a key role in the cultural and artistic exchanges of the Meiji period. Bunzaburō’s leadership at Goseda Juku, which he took over in 1880 after Goseda Hōryū’s health began to decline, marked another important chapter in his career. As head of the school, Bunzaburō continued teaching his students how to fuse Western techniques with traditional Japanese themes, passing on the skills he had learned.

One of his most notable disciples was Yokoyama Taikan, a future leader of the Nihonga movement. Taikan studied under Bunzaburō at the Tokyo English School in 1885, focusing on pencil drawing. Although Taikan would later become famous for his contributions to Nihonga, a style rooted in traditional Japanese aesthetics, Bunzaburō’s influence on his early artistic development was undeniable. Bunzaburō’s other students, many of whom also embraced the fusion of Western and Japanese styles, played key roles in shaping the future of modern Japanese painting.

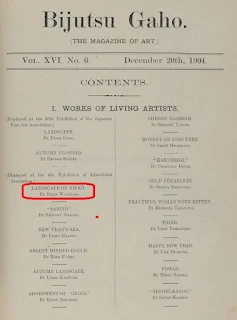

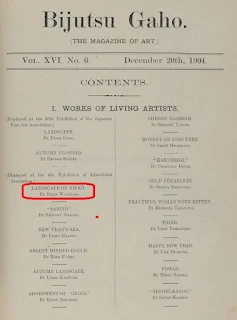

In 1889, Bunzaburō was one of the founding members of the Meiji Bijutsu Kai (明治美術会), an art association that aimed to promote Western-style painting in Japan. This organization played a crucial role in legitimizing Western techniques in the Japanese art world and provided a platform for artists like Bunzaburō to showcase their work. His involvement underscored his role in advocating for the acceptance of Western-style painting during a time of great cultural change.

Bunzaburō’s legacy extends far beyond his own artwork. As both an artist and a teacher, he helped shape the course of modern Japanese painting by blending Western techniques with traditional Japanese themes. His leadership at Goseda Juku and his influence on artists such as Yokoyama Taikan ensured that his teachings would continue to resonate in the generations that followed. Through his efforts to bridge Eastern and Western artistic traditions, Bunzaburō’s impact on Japanese art remains significant, and his contributions to the Meiji-era art movement continue to be celebrated.

No comments:

Post a Comment