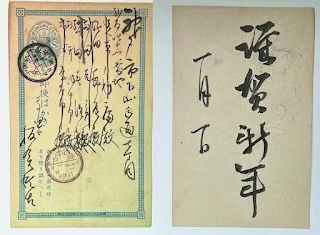

This New Year's card, postmarked Bitchu, Takahashi, and dated January 1, 1890, was sent by Sugi Chūzaburō and his eldest son, Sugi Sadatsugu. The Sugi family, although of samurai status, held a modest annual stipend of 60 koku. Chūzaburō's younger son, Sugi Sadamitsu, is noted in Wikipedia as a Japanese naval hero for undertaking two suicidal missions during the Russo-Japanese War.

Maeda Yoshihiko (前田吉彦, 1849–1904), also known by his artistic name Gizen (蟻禅), was a Japanese Western-style painter of the Meiji period, though he remains largely unknown outside Japan. This blog presents previously unpublished insights into his life and work through correspondence from historical figures and fellow artists of the time, offering a unique glimpse into his personal connections and the cultural context of the era.

Thursday, November 28, 2024

備中松山藩士60石取、杉忠三郎と杉貞次

Wednesday, November 27, 2024

清水比庵の父、備中高梁の清水質から前田吉彦宛の年賀状

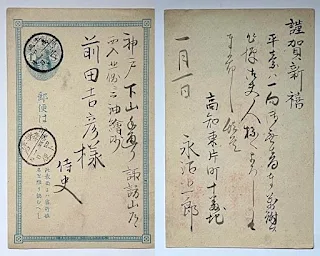

The first postcard was sent from Bitchu, Takahashi by Shimizu Tadashi (1860-1905) to Maeda Yoshihiko (1849-1904) on January 2, 1889. It is a typical New Year's greeting card. The second card dated July 3, 1889 is interesting, as it refers to Maeda as an "oil paint artist" (油画師, abura-e-shi).

While little is known about Shimizu Tadashi, it is documented that he was an educator and civil servant in Takahashi, Okayama. He played a significant role in assisting Shigeko Fukunishi (福西志計子, 1848-1898) in establishing Junsei Girls' School (順正高等女学校) in 1881. Occasionally, he used the pen name "Keigai."

Shimizu Tadashi's son, Shimizu Hian (清水比庵, 1883-1975), later gained prominence as a poet, calligrapher, painter, and politician. His artworks are featured in many American museums, including the Smithsonian and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. At the time this postcard was mailed, Shimizu Hian was only six years old. The message side of the postcard is printed.

Tuesday, November 26, 2024

永沼小一郎 (牧野富太郎の教師) 1889年の熊本地震

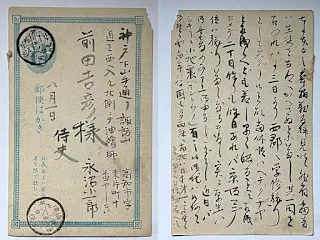

The sender of these two cards is Naganuma Koichirō, a knowledgeable teacher well-versed in science and botany. He was a mentor to Makino Tomitarō (牧野富太郎, 1862–1957), who later became a distinguished botanist often referred to as the "Father of Japanese Botany." It's interesting to note that Makino was also an artist. He initially created botanical illustrations in the traditional Japanese style, but his artwork later evolved to reflect Western influences.

Both cards are dated 1889 and were sent from Kōchi, Tosa. One is an ordinary New Year's greeting card. However, the second card, postmarked August 1, 1889, is quite intriguing. Naganuma mentions taking his students on a trip and describes feeling a mild earthquake during their travels. Given the date, he was likely referring to the 1889 Kumamoto earthquake on July 28, which affected the western part of Kumamoto.

Sunday, November 24, 2024

太田武和 (太田恥堂) 油画先生 - 油画師

Saturday, November 23, 2024

明治24年備中成羽 石田徳三郎 - 石田行道

Friday, November 22, 2024

明治23年と24年の明治学院の上原季五郎

Both of these cards were sent by Uehara Kigoro. We believe he was a student at Meiji Gakuin. Meiji Gakuin University began as Dr. Hepburn's English school, "Hepburn Juku," founded in 1863. Tsukiji Dai Gakko [Tsukiji College] was renamed ‘Meiji Gakuin’ in 1886 and, in 1887, the Tokyo government approved a move of its campus from Tsukiji to its present location at Skirokane, Tokyo. For another card from Uehara, see our post dated Oct. 7, 2024.

Thursday, November 21, 2024

森田専一(数学教師) 前田吉彦宛の明治20年のはがき

These two cards were sent to Maeda Yoshihiko on January 1, 1887, from Osaka and on August 8, 1887, from Higashi Suma, Settsu, by Morita Senichi (森田専一). He is mentioned on a site specializing in Mori Kinseki (森琴石, 1843-1921), a Nanga painter and copperplate engraver: https://www.morikinseki.com/chousa/h1606.htm

"After dropping out of Tokushima Western School and Sumoto Nisshin School, he was appointed as an assistant instructor in mathematics and bookkeeping in July of Meiji 16 (1883). He left the position in July of Meiji 37 (1904) after 27 years of service. In Meiji 29 (1896), he became involved with the new alumni magazine "Rikuryo" as its publisher and editor since its inception. He is also said to be the designer of the "Rikuryo" school emblem."

As for the contents of these postal cards, they are illegible to us.

Wednesday, November 20, 2024

本山彦一 (大阪毎日新聞社長) から前田吉彦宛のはがき

This postal card is postmarked in Osaka, dated September 9, 1889. It was sent by Motoyama Hikoichi (本山彦一, 1853-1934). He was a key figure in Japanese media and politics during the late 1800s and early 1900s. He helped shape modern journalism in Japan through his work with the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, one of the country's leading newspapers. Under his leadership, the newspaper grew in importance and adopted new technologies, becoming a major player in Japanese media.

Besides his work in journalism, Motoyama was also a politician. He served in the House of Representatives in the Imperial Diet, where he used his media experience to push for press freedom and democratic values. His dual roles as a journalist and politician allowed him to make a significant impact on Japanese society, promoting the free flow of information and modernization.

Monday, November 18, 2024

Bunzaburo Watanabe (Bizan) from Goseda School in Tokyo in 1889

渡辺文三郎 (薇山) 明治22年東京五姓田塾からのはがき

The discovery of this postal card, along with other cards written by Watanabe Bunzaburō that will be introduced in time, is nothing short of remarkable. Sent to Maeda Yoshihiko and remaining unseen for 135 years, they offer invaluable insight into a crucial period of Western-style painting.

This card bears a postmark from 下谷東京 (Shitaya, Tokyo), an area near present-day Ueno Park and close to Asakusa, where Goseda Hōryū's art class was located. Sent on May 29, 1889, Bunzaburō listed his address as #68 Naka-Okachimachi, Shitaya, Tokyo. It appears he ran out of space, writing his name as 渡辺文三, omitting the 郎.

Just a few weeks earlier on May 1, 1889, Watanabe Bunzaburô, along with Goseda Yoshimatsu (五姓田義松), Yamamoto Housui (山本芳翠), Goseda Hōryū (五姓田芳柳), Goseda Hōryū II (五姓田芳柳 二代目), Watanabe Yūkō (渡辺幽香), and three dozen other artists attended the inaugural meeting of the Meiji Art Society.

Sunday, November 17, 2024

Newly Discovered 1889 Artwork by Shinzo Kawai

河合新蔵のイラスト新発見、明治22年の前田吉彦宛の年賀状

From our review of the available correspondence, it appears that Kawai Shinzo preferred using the name 河合新造 rather than 河合新蔵, at least prior to his emergence as a prominent artist.

This postal card bears the postmark of Osaka, dated January 2, 1889. It was sent from Minami-honmachi, Osaka (大阪 南本町1丁目) by Kawai Shinzo (河合新蔵, 1867–1936) prior to his rise to prominence as a Western-style painter, while he was still studying under the guidance of Maeda Yoshihiko (前田吉彦) in Kobe.

This New Year's greeting card features an extensive message, which, while potentially of historical significance, remains inaccessible due to the complexities of the Meiji period script. Nevertheless, the card is notable for Kawai's ink drawing of a young dandy—likely a self-portrait—dressed in a double-breasted tunic. The figure is depicted in a slightly bowed stance, removing his derby hat as a mark of respect. This image offers valuable insight into Kawai's early artistic style. Given that this collection includes other postcards written by Kawai to Maeda after he relocated to Tokyo in 1891 to continue his studies, this particular card serves as an important link in understanding his development during that time.

Kawai Shinzō (1867–1936)

Introduction

Kawai Shinzō (1867–1936) was a prominent Japanese painter who made significant contributions to the development of modern Japanese art, particularly in the realm of watercolor painting. Throughout his life, Kawai was influenced by both traditional Japanese artistic methods and Western techniques, which he encountered during his studies abroad. His involvement with various art societies and exhibitions, as well as his innovations in watercolor, solidified his place in the history of Japanese art during the Meiji and Taishō periods. This post explores Kawai Shinzō’s life, education, career, and artistic achievements, focusing on the key milestones that shaped his work.

Early Life and Education

Kawai Shinzō was born on May 27, 1867, in Osaka, Japan, during the Keiō era. His initial artistic education was grounded in Japanese traditional painting. He studied under the guidance of two notable artists of the time: Suzuki Raisai and Maeda Yoshihiko, both of whom introduced him to Western-style painting. This early exposure to Western techniques would influence Kawai’s later work, as he blended Japanese and Western styles in his practice.

In 1891, at the age of 24, Kawai moved to Tokyo to continue his artistic education. He studied at Goseda Yoshiryu’s (五姓田芳柳) studio and later with Koyama Shōtarō at the Futōsha (不同舎). These mentors helped him refine his skills in Western-style oil painting while also encouraging a focus on realism. During his time in Tokyo, Kawai became increasingly interested in the evolving art scene, especially as Japan began to modernize and adopt more Western influences.

Studies Abroad

Kawai’s artistic development took a pivotal turn in 1900 when he, along with other artists such as Mitsutani Kunishirō and Kanokogi Takashiro, traveled to America. The trip marked the beginning of Kawai’s international exposure, which would further shape his work. In 1901, Kawai moved to France to study at the prestigious Académie Julian and Académie Colarossi in Paris. These institutions were instrumental in providing him with a solid foundation in Western academic painting, allowing him to master various techniques, including realism and impressionism.

Kawai's time in Europe exposed him to the Parisian avant-garde and a variety of Western art movements, but his work remained distinctly Japanese in its use of traditional subject matter, including landscapes and nature. After spending several years in Europe, Kawai returned to Japan in 1904, settling in Kyoto. He continued to pursue his interest in modern painting while maintaining his connection to traditional Japanese art forms.

Return to Japan and Career Developments

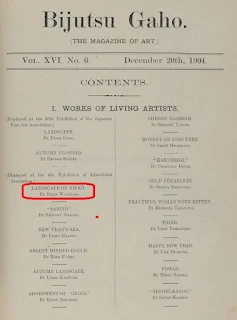

Upon returning to Japan, Kawai became involved in the burgeoning Japanese modern art scene. He joined the Pacific Painting Society (太平洋画会) in 1904, exhibiting his works at the society’s third exhibition. Kawai’s involvement in such societies helped solidify his reputation as a member of the new generation of Japanese artists who sought to incorporate Western techniques into their work while retaining elements of traditional Japanese aesthetics.

In 1906, Kawai co-founded the Japanese Watercolor Painting Research Institute (日本水彩画研究所) alongside prominent figures like Ōshita Tōjirō. This organization was dedicated to promoting watercolor as a legitimate and respected medium in Japan, and it played a key role in the rise of watercolor painting during the late Meiji and Taishō periods. Kawai’s own work during this time was characterized by his ability to capture the nuances of nature, often using watercolors to depict landscapes, flora, and animals with a delicate yet expressive touch.

Kawai was also active in major exhibitions in Japan. He participated in the Bunten (文展) and Teiten (帝展) exhibitions, which were important government-sponsored events that helped establish the careers of many artists. In 1907, he exhibited his piece “Mori” (Forest) at the first Bunten exhibition, followed by another important watercolor piece, “Ryokuin” (Green Shade), at the second Bunten exhibition in 1908. His continued success in these exhibitions confirmed his place as one of Japan’s leading watercolor painters.

Involvement in Art Societies and Achievements

Kawai Shinzō’s commitment to watercolor painting led him to become a founding member of the Japanese Watercolor Painting Association (日本水彩画会) in 1913. His active participation in this organization and his success in exhibitions further cemented his reputation as one of the leading figures of Japan’s watercolor movement. In the same year, Kawai received third prize at the 7th Bunten Exhibition for his work “Poplar and Summer Oranges” (ポプラ―と夏蜜柑). This achievement showcased his ability to combine technical skill with artistic sensitivity, a hallmark of his approach to watercolor painting.

Throughout his career, Kawai’s works continued to be featured in various official exhibitions. He was a member of the Imperial Exhibition (帝展) and the Second Division, which was a prestigious recognition within the Japanese art world. His association with these exhibitions ensured that his works were widely recognized and appreciated during his lifetime.

Later Years and Legacy

Kawai Shinzō spent his later years residing in Kyoto, in a district called Murasakino, where he continued to paint until his death. He passed away on February 15, 1936, at the age of 68. His contributions to Japanese watercolor painting and his role in the development of modern Japanese art left a lasting legacy.

Kawai’s work remains an important example of the fusion between traditional Japanese techniques and Western artistic influences. He was one of the key figures in the rise of watercolor painting in Japan, and his works are still regarded as masterpieces of the genre. Through his participation in art societies, his role as a mentor to younger artists, and his consistent output of high-quality works, Kawai Shinzō helped define the trajectory of Japanese art during a period of intense cultural and artistic transformation.

Conclusion

Kawai Shinzō’s life and career represent the transition of Japanese art from traditional practices to the embrace of modern, Western-inspired techniques. His exposure to both Japan’s rich artistic heritage and Western artistic movements, particularly during his time in France, played a central role in the development of his distinctive style. As a key member of Japan’s watercolor movement and a committed educator, Kawai left an indelible mark on the history of modern Japanese painting. His legacy continues to inspire artists and scholars today, and his work remains an integral part of Japan’s artistic canon.

明治22年広島の歯科医、富永省吾から前田吉彦宛の年賀状

Postmarked December 31, 1889, in Hiroshima, this New Year's greeting card was sent to Maeda Yoshihiko from Tominaga Shogo (富永省吾). Tominaga, who opened Hiroshima City's first dental clinic in 1886, holds the distinction of being Hiroshima Prefecture's first practicing dentist. In March 1887, under the initiative of several prominent doctors, including Dr. Shizuo Goto, the "Hiroshima Medical Association" was established.

Saturday, November 16, 2024

明治23年備中下原の石田徳三郎から前田吉彦宛の礼状

On January 1, 1890, Ishida Tokusaburo (石田徳三郎) of Shimobara, Bichu (present-day Okayama) sent a postal card to Maeda Yoshihiko (前田吉彦) and Udagawa Kingo (宇田川謹吾) in Kobe. The identities of Udagawa Kingo and the sender, Ishida Tokusaburo, remain unknown, though the card appears to express gratitude. Tokusaburo provided his return address as 川上郡 東成羽村 大字星原 (Ooza Hoshibara, Higashi Nariwason, Kawakami-gun).

Interestingly, there is a touch of yellow oil paint above the Kobe postmark. Maeda must have been working on a painting when he handled this postcard.

Thursday, November 14, 2024

明治23年伊勢の笹田雅之から前田吉彦宛の年賀状

Postmarked in Ise (Mie Prefecture) on January 3, 1890, this card was sent by Sasada Masayuki. The greeting card employs a similar printing process to the card below, utilizing purple ink. Four or five characters are written in black ink over the purple print, but we are unable to decipher them. It is unclear if these characters were meant to correct a part of the printed message or serve another purpose.

Interestingly, the printed side of this card is upside down; instead of ↑ ↑, it is ↑ ↓. Sending such a misprinted card might seem improper and disrespectful. Did the printer or Sasada notice the error? Regardless of their awareness, they wouldn't have discarded the cards, as each one was worth one sen. However, I am confident that the printer did not charge Sasada for the printing costs.

Wednesday, November 13, 2024

前田吉彦宛の明治23年広島の古田からの年賀状

We believe the sender of this stationery card, postmarked in Hiroshima on January 4, 1890, was 友田美喬 (Tomoda Yoshitaka), Army infantry officer. What makes this card particularly interesting is its backside, which features an unusual ink color commonly associated with mimeograph-printed materials. However, since mimeographs were not widely used until some years later, it is likely that a different printing method was employed in this case.

Monday, November 11, 2024

播磨三草の木本常次郎 (数学者)

This New Year's greeting card was sent to Maeda Yoshihiko by Kimoto Tsunejirō from Mikusa, Harima, on January 2, 1889. Information about Kimoto Tsunejirō is limited, with only a few mentions online, including his resignation from an unspecified institution and a reference to him in a scholarly work.

Sunday, November 10, 2024

Itakura Nobunao (板倉信古, 1846–1912)

This New Year's greeting card is quite unusual, as it is addressed to six people, but two vertical lines nearly obliterate two of the names. Additionally, two more vertical lines are drawn to enclose and highlight Maeda Yoshihiko's name.

The card was sent from Takahashi, Bitchū Province (びっちゅう, Bitchū), postmarked December 31, 1891, and arrived the following day in Kobe. Interestingly, it is addressed to Number 7 instead of Maeda's usual Number 6, which I believe was an error by the sender.

Itakura Nobunao (板倉信古, 1846–1912): From Samurai to Civic Leader

Itakura Nobunao, also known as Nobufuru, was born in 1846 in Honchō, part of the Bitchū Matsuyama Domain (now Takahashi, Okayama). He was born into a mid-ranking samurai family with a stipend of 300 koku, a level that ensured both martial training and formal education.

Later in life, Nobunao was adopted into the Itakura clan, the ruling family of Bitchū Matsuyama. This type of adoption was common in elite circles and served to maintain family lines and influence. For Nobunao, it meant a major step up in status, tying him to the leadership of the domain during the late Tokugawa period.

Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868 and the abolition of the feudal system, Nobunao shifted to a role in public administration. He became mayor of Takahashi (formerly Bitchū Matsuyama), where he worked on infrastructure, education, and local economic reforms. His career path—from samurai to adopted heir to modern mayor—reflected the broader transitions underway in Japan during this period.

Nobunao died on January 7, 1912, at the age of 66. His life illustrates how individuals from the samurai class adapted to Japan’s modernization. Adoption allowed him to move from a 300-koku family to one that ruled over 50,000 koku, placing him in a position of leadership. As mayor, he helped guide Takahashi through its transformation from a former castle town into a modern municipality.

Nobunao’s story is a case study in how former samurai applied their training and sense of duty to new roles in a rapidly changing society. His legacy is one of continuity through change—maintaining traditional values while embracing new responsibilities in a modern nation.

Friday, November 8, 2024

前田吉彦はこのような小学生用の美術教教科書を書いていた

These grade school art textbooks, written by Maeda Yoshiko, are published by Yoshioka Heisuke (see post from October 31).

前田吉彦宛の藤井忠弘 (挿絵画家)

Postmarked on January 2, 1890, and May 28, 1890, in 武蔵東京本所 (Musashi Tokyo Honjo), these cards were sent by 藤井忠弘 (Fujii Tadahiro). He is believed to have been an artist, specializing in illustration and cartography, active during the Meiji era.

Thursday, November 7, 2024

明治時代の教育者 飯田正宣から前田吉彦 洋画家宛のはがき

This postal card was sent on January 5, 1889 from Utsunomiya, Tochigi by Iida Masanobu. It has the usual preprinted New Year's message along with handwritten note, which we are not able to read. Iida Masanobu was involved in the establishment of teacher training institutions to ensure that educators were well-prepared to teach the new curriculum. His work in this area helped professionalize teaching and elevate the status of educators in Japan.

Sunday, November 3, 2024

平瀬與一郎 (貝類研究家)から前田吉彦への年賀状 明治22年

Saturday, November 2, 2024

1890年 藤本安兵衛 米穀商より前田吉彦へのはがき

This postcard was sent by Fujimoto Yasubei, a rice dealer from Kobe, on May 24, 1890. He is mentioned in the publication Hyogo-ken Jinbutsu-hyo (兵庫県人物評), which was released between 1892 and 1896. This work lists and describes the prominent figures of Hyogo Prefecture (see photo).