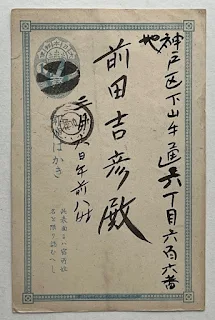

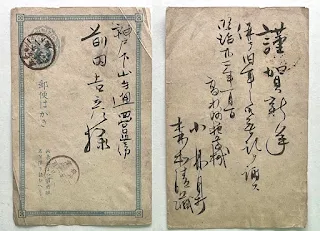

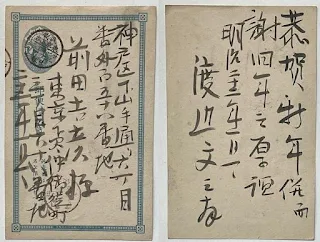

We recently came across a postal card that offers a rare look into the post-feudal connections of the former retainers and ruling class of the Bitchū Matsuyama Domain. The card was sent from 板倉勝弼 / 家扶, household of Itakura Katsusuke (1846–1896), the last daimyo of the domain. Dated September 25, 1889, and postmarked in Shitaya, Tokyo, it lists his return address as 3-chome, Yushima Tenjin-chō, Hongō Ward. The card is addressed jointly to Maeda Yoshihiko and Adachi Toshitsune (足立利庸), both of whom were associated with the Itakura clan.

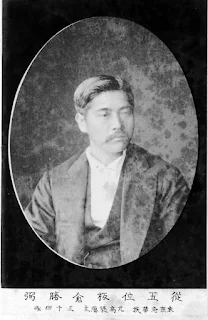

Itakura Katsusuke: From Daimyo to Citizen

Itakura Katsusuke served as the final lord of the Bitchū Matsuyama Domain, later renamed Takahashi Domain in 1869. Like many former daimyo after the Meiji Restoration, he was stripped of his feudal title but permitted to retain a portion of his former holdings. He adapted to the new era by moving to Tokyo and taking on a civilian life under the kazoku peerage system. His presence in Tokyo, and his continued correspondence with former retainers like Maeda and Adachi, shows how the relationships forged under the han system often endured even after the social structure itself had been dismantled.

Katsusuke’s connection to his former retainers appears to have remained strong. This card, sent nearly two decades after the dissolution of his domain, demonstrates that he still maintained personal ties with those who had served under him—something not always visible in historical records but revealed here through everyday communication.

Adachi Toshitsune and His Role in Meiji Education

Born in 1853 in Nakanomachi, Takahashi (now part of Okayama Prefecture), Adachi Toshitsune was a samurai by birth and an educator by calling. He studied at the domain school Yūshūkan under Kamata Genkei and Kawada Ōkō, then went on to graduate from Tokyo Normal School. He returned to his home region and worked in elementary education across Okayama and Hyōgo prefectures for more than 40 years.

Adachi became a respected figure in local education, eventually serving as a circuit instructor, overseeing multiple schools—a role similar to what we now call a regional education supervisor. His contributions helped shape early Meiji-era education in the countryside, where trained teachers were still rare. In his later years, he lived in Suma, Hyōgo Prefecture. A poem he wrote at age 83 is preserved in the archives of Takahashi High School, and his writings are also found in local anthologies.

Shared Roots, Enduring Ties

Maeda Yoshihiko, another recipient of the card, was a Western-style painter and art educator based in Kobe. Like Adachi, he came from a former retainer family of the Itakura clan. The card illustrates how these men—once part of a feudal structure—carried those relationships well into the Meiji period. Though their professions had changed, they remained connected through personal bonds and shared history.

This single card helps confirm what we’ve suspected: the Itakura, Maeda, and Adachi families were not just historically connected—they actively stayed in touch, well into the 1880s. It’s a small but meaningful window into how former domain networks functioned behind the scenes in Meiji Japan.