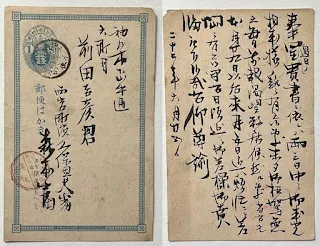

This 1889 postcard, sent locally in Kobe on August 5, is addressed to 前田吉彦先生 (Maeda Yoshihiko-sensei), with the familiar 六要堂 (Rokuyōdō) notation we’ve noted before. An intriguing feature is the unidentified character to the left of 生 (sensei), appearing almost as part of the kanji. Its purpose is unclear—possibly a personal mark or an obsolete abbreviation. The sender’s information, written right to left in the Meiji-era style, reads 宇治川山西 (Ujigawa Yamanishi), likely referencing the Uji River (or a local Kobe waterway) and possibly the surname Yamanishi, though this remains uncertain. The message appears to be a routine summer greeting, offering a glimpse into everyday social exchanges in late 19th-century Japan.

Maeda Yoshihiko (前田吉彦, 1849–1904), also known by his artistic name Gizen (蟻禅), was a Japanese Western-style painter of the Meiji period, though he remains largely unknown outside Japan. This blog presents previously unpublished insights into his life and work through correspondence from historical figures and fellow artists of the time, offering a unique glimpse into his personal connections and the cultural context of the era.

Sunday, April 27, 2025

Thursday, April 24, 2025

Nakajima Seikei 中島静溪 Forgotten Meiji Artist 1889

When we first published our post on October 16, 2024, titled 1889年のはがき: 前田吉彦宛の美術用品の話, we were unable to determine Nakajima’s first name, leaving his identity uncertain. It was only later, upon identifying his connections not only to Maeda Yoshihiko but also to Masuda Matsuyuki, that a missing piece of the puzzle came into focus. He was one of three artists involved in the 1891 Art Exhibition, alongside Maeda Yoshihiko and Masuda Matsuyuki.

In this postal card, Nakajima refers to クラヒオン チョーク (kurahion chōku), a term that appears to be a transliteration of a foreign phrase, likely describing an art material used by Japanese painters during the Meiji era. クラヒオン (kurahion) is probably derived from the French word crayon, which can refer to a pencil, colored pencil, or various other drawing tools such as pastel sticks. チョーク (chōku) is the Japanese transliteration of “chalk”.

Taken together, クラヒオン チョーク likely refers to a type of drawing medium akin to chalk crayons or pastel chalks. During the Meiji period, Japanese artists were increasingly introduced to Western art supplies and techniques, adopting a variety of tools such as crayons and chalks into their own practices. It’s worth noting that at the time, terminology for art materials in Japan had yet to be standardized. As a result, phonetic approximations of foreign words were commonly used, producing transliterations like “クラヒオン” for “crayon.”

神戸油絵と書画の展観 1891 Kōbe Aburae to Shoga no Tenkan

February 10, 1891

"Exhibition of Oil Paintings and Calligraphy — On the occasion of the Academic Encouragement Association meeting to be held tomorrow, the 11th, at Kobe Elementary School, there will be an exhibition of oil paintings and modern calligraphy, along with an on-site calligraphy demonstration starting at noon. The event is organized by three individuals: Maeda Yoshihiko, Masuda Matsuyuki, and Nakajima Seikei. The exhibited works will remain open to public viewing until 3 p.m. the following day, the 12th."

"油絵と書画の展観―明11日神戸尋常小学校内において学業奨励会の挙あるに際し 同日正午12時より油絵と近世書画の展観ならびに席上揮毫を催すよし 此の発起人は前田吉彦、増田松之、中島静溪の三氏にて右油絵と書画は翌12日午後3時迄縦覧を許しますと"

The above notice of exhibition was published on February 10, 1891 in 神戸又新日報 (こうべゆうしんにっぽう), Kobe newspaper, according to morikinseki.com. It is a comprehensive digital archive and research platform dedicated to Mori Kinseki (森琴石, 1843–1921), a prominent Meiji-era Japanese artist known for his contributions to Nanga (traditional Southern Chinese-style painting) and copperplate etching. The website serves as a critical resource for scholars, art enthusiasts, and historians, offering detailed insights into Mori’s life, works, and cultural influence.

The newspaper article confirms that Maeda Yoshihiko, Masuda Matsuyuki, and Nakajima Seikei collaborated closely, solidifying their bonds not only as fellow artists but also as personal friends. While this discovery illuminates their shared creative endeavors, Nakajima Seikei himself remains a historical enigma—his life and work seemingly erased by time.

Monday, April 21, 2025

A Postcard from the Kawasaki Shipyard – Kobe, 1891 川崎造船所

This postcard, postmarked July 4, 1891, was sent from the Higashi Kawasaki-chō district of Kobe to Maeda Yoshihiko, addressed via Rokuyōdō at 6-chōme, Shimoyamate-dōri. The sender was Kawasaki Zōsenjo—known in English as Kawasaki Shipyard—which at the time was still in its early decades of operation. Its presence in Kobe would eventually become central to Japan’s growing naval industry.

Stamped in red ink is the name and address of the company, along with a note advertising its services: shipbuilding machinery and other equipment, available either newly manufactured or repaired according to customer needs. This sort of messaging gives a glimpse into the commercial tone of the period, and how major industrial firms were beginning to establish both infrastructure and customer relationships across Japan.

The Kawasaki Shipyard would go on to play a major role in modern Japanese shipbuilding. In the decades that followed, it produced many important vessels for the Imperial Japanese Navy, including battleships like Ise and Haruna, aircraft carriers such as Akagi and Kaga, and a range of large submarines. But in 1891, this card shows a company still positioning itself as a capable and reliable supplier of marine machinery.

The handwritten message on the reverse is formal and somewhat abbreviated, written in a flowing style that makes full transcription difficult. However, it contains the usual expressions of courtesy and acknowledgment—phrases suggesting that the sender was replying to or thanking Maeda for a previous letter or assistance. It’s polite, reserved, and businesslike, in keeping with correspondence between professionals.

As with other cards addressed to Maeda, this one ties into a small but growing body of documents that help flesh out his network and standing in Meiji-era Kobe.

Red Stamp:

神戸市 東川崎町 (Kobe-shi, Higashi Kawasaki-chō)

造船機気其他諸器械 (Shipbuilding machinery and other equipment)

川崎造船所 (Kawasaki Shipyard)

新製〇繕 御好ニ応ズ (New and repaired items available to order)

Thursday, April 17, 2025

秋山貫一 Akiyama Kan’ichi, 隠岐一慎 Oki Isshin, 船井長四郎 Funai Choshiro, 赤木義彦 Akagi Yoshihiko

Four postcards addressed to Maeda Yoshihiko were sent from Settsu Kobe between 1890 and 1891. The postmark dates are: January 27, 1890; October 4, 1891; December 14, 1891; and December 25, 1891. Notably, the card dated October 4, 1891, bears a double postmark—an uncommon occurrence.

first top left: Akiyama Kan’ichi (秋山貫一) Ukiyo Manga (浮世漫画) Artist

bottom left sent by 隠岐一慎, (Oki Isshin)

second from top right: 船井長四郎 Funai Choshiro

bottom right, 赤木義彦, Akagi Yoshihiko is listed as the author of a book titled 《日本火災要論 上巻》 ("Essentials of Fire Disasters in Japan, Vol. 1"), which likely deals with fire prevention, urban safety, or police administration related to fire management — a key responsibility of the police during that period.

Samurai Roots: Akagi was originally a samurai of the Okayama Domain (岡山藩士).

Early Police Service: When the Tokyo Metropolitan Police (警視庁) was founded in Meiji 7 (1874), Akagi was appointed a Junior Police Inspector (少警部).

Seinan War (1877): He served under Kawaji Toshiyoshi (川路利良), the prominent head of the police during the Satsuma Rebellion (西南戦争). His role likely involved field operations or intelligence gathering during the conflict.

Tuesday, April 15, 2025

Tsuji Chōzaemon (辻長左衛門) 小豆澤写真油絵

All five cards were sent by Tsuji Chōzaemon (辻長左衛門), an artisan whose name also appears in a printed art catalog titled 『小豆澤写真油絵』 (Azukizawa Shashin Abura-e), compiled by Azukizawa Ryōichi(小豆澤亮一, 1848–1890). Despite its title, the catalog was not a product of a photo studio. Rather, it was a curated collection of artworks—likely published after October 1885 (Meiji 18), which appears to be the earliest date for the items included. The catalog featured a wide range of works: photographs, oil paintings, lacquerware, ceramics, metalwork, textiles, and other decorative arts.

Tsuji Chōzaemon’s contribution was the 金焼着瑠璃鐘 (Kin’yaki Chakururi-shō), a bell decorated with gold-fired ornamentation and lapis-blue glaze. Whether intended for ceremonial or ornamental use, the piece exemplifies the high level of craftsmanship found throughout the catalog. Other featured works include lacquered writing boxes, ivory figurines, patterned leather, Kutani vases, silver incense burners, Meiji-era wallpapers, and even coffee sets by renowned enamelist Tōkawa Sōsuke.

Together, the postcards and the catalog entry shed light on the vibrant, interconnected world of Meiji-era artists and artisans. Figures like Maeda and Tsuji were part of a shared creative environment where correspondence, exhibition, and craft publication helped define both personal relationships and the evolving role of art in modern Japan.

Saturday, April 12, 2025

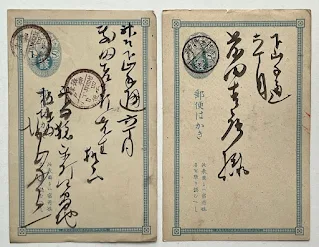

August 8, 1889 聞信寺 百済流情

八月四日午後発 August 4 Afternoon

大阪市東区南久太郎町四丁目 4-chome, Minamikutarō-machi, Higashi Ward, Osaka City

聞信寺 百済流情 Monshin-ji Temple, Kudara Ryūjō

Kudara (Hyakusai?) was likely a monk.

Friday, April 11, 2025

1889 森本富 and 足立利庸

This postcard bears a postmark from 摂津西ノ宮 (Settsu Nishinomiya) in Hyogo Prefecture and was sent by an individual named Morimoto Tomi—森本富. The message appears to outline travel plans, but what makes this card particularly noteworthy is how Morimoto addresses Maeda Yoshihiko: using the suffix "君" (kun).

This choice of address suggests one of two possibilities:

A close personal friendship between Morimoto and Maeda, as "kun" is often used among peers or by superiors toward younger or subordinate males.

Morimoto held a higher social or professional status than Maeda, granting him the familiarity to use "kun."

This is only the second known instance of Maeda being addressed this way in correspondence. For the previous example, refer to our October 13, 2024 post.

The second card, dated June 27, 1889, was sent from Kobe and addressed to Maeda while he was staying at Morimoto’s residence at Nishinomiya Hamakubo-chō 18-ban (西ノ宮町濱久保町十八番). The sender’s name is Adachi Toshitsune (足立利庸). Curiously, Maeda is addressed as 前田吉彦殿 rather than the more customary 様. There appears to be some connection between the two cards, though the nature of that relationship remains unclear.

Adachi Toshitsune and His Role in Meiji Education

Born in 1853 in Nakanomachi, Takahashi (now part of Okayama Prefecture), Adachi Toshitsune was a samurai by birth and an educator by calling. He studied at the domain school Yūshūkan under Kamata Genkei and Kawada Ōkō, then went on to graduate from Tokyo Normal School. He returned to his home region and worked in elementary education across Okayama and Hyōgo prefectures for more than 40 years.

Adachi became a respected figure in local education, eventually serving as a circuit instructor, overseeing multiple schools—a role similar to what we now call a regional education supervisor. His contributions helped shape early Meiji-era education in the countryside, where trained teachers were still rare. In his later years, he lived in Suma, Hyōgo Prefecture. A poem he wrote at age 83 is preserved in the archives of Takahashi High School, and his writings are also found in local anthologies.

Thursday, April 10, 2025

Unreadable Postal Card to Maeda Yoshihiko – November 8, 1891

The date is derived from the Kobe postmark, as the originating postmark is too faint and incomplete to decipher. The sender’s name, message, and return address are entirely illegible. However, as we continue examining this collection of postcards, we may encounter another from the same sender with identifiable details that could help clarify this one.

Tuesday, April 8, 2025

Yamana Ukai (山名迂介) Uchida Mohachi (内田茂八) Watanabe Yūkō (渡辺幽香) Relations?

These two postcards offer rare and compelling insights into the network of Japanese artists during the Meiji period, subtly “knitting together” personal and professional relationships that have otherwise gone undocumented.

Yamana Ukai, April 17, 1889

Postmarked in Shitaya, Tokyo (下谷東京), this postcard represents one of only two known records of the elusive artist Yamana Ukai (山名迂介), a figure absent from formal art historical archives despite extensive research. Sent from the residence of Watanabe Bunzaburō at 3-68 Naka-Okachimachi, Shitaya, and addressed to Maeda Yoshihiko, the card contains a respectful reference to Watanabe as 渡辺老兄 (Watanabe Rōkei, “esteemed elder Watanabe”), suggesting a senior-junior or master-apprentice relationship. While this establishes Yamana’s association with Watanabe’s artistic circle, much of the card’s content remains undeciphered for now.

Yamana Ukai, February 7, 1889

The earlier of the two cards, postmarked in Osaka, lists the return address of Uchida Mohachi (内田茂八) at 7-chōme Nakanoshima, Kita-ku—indicating Yamana was staying there at the time. Remarkably, this card includes two references to Watanabe Yūkō (渡辺幽香), a talented female artist. Her name appears first as 幽香女史 (Yūkō Joshi), using the honorific joshi for educated or professional women (circled in red on the original), and again as 渡辺幽香, spaced in signature-like fashion at the bottom-left corner, implying direct involvement.

Uchida Mohachi was likely an artist in his own right with a number of pupils. In fact, Watanabe Bunzaburō refers to 内田茂八門—the school or artistic lineage of Uchida Mohachi—when discussing Yamana Ukai, reinforcing the impression that Yamana was part of Uchida’s circle as well (see photo below).

Adding to the intrigue is the historical context: just two weeks prior to the Osaka postmark, the city hosted its first lithography and copperplate society meeting at the nearby Jiyūtei Hotel. Given Watanabe Yūkō’s known training in both techniques under Matsuda Rokuzan (松田緑山), and the proximity of Uchida’s address to the meeting site, it’s plausible—though speculative—that Uchida, Yamana, and Yūkō all attended. The double mention of Yūkō to Maeda Yoshihiko, who likely knew her reputation, raises further questions. Could this hint at collaborative work or a planned exhibition now lost to history?

This unexpected find not only revives Watanabe Yūkō’s faint historical presence but also offers a rare glimpse into the possible participation of women in early Meiji-era printmaking circles—a small but valuable clue in the broader reconstruction of women’s roles in Japanese art.

Watanabe Yūkō (渡辺 幽香, 1856 – 1942) was a pioneering Japanese artist of the Meiji period, known for her Western-style (yōga) paintings. Born into an artistic family in Edo (now Tokyo), she was the daughter of Goseda Hōryū (五姓田 芳柳, 1827–1892), a prominent painter, and the sister of Goseda Yoshimatsu (五姓田 義松, 1855–1915), also an accomplished artist. Her early exposure to art within her family significantly influenced her career.

Yūkō received her initial training in painting from her father and brother, immersing herself in the techniques of Western-style art. This familial mentorship was a common pathway for women artists of that era, as formal art education institutions were predominantly male-oriented. In 1869, Yūkō began a series of lithographs titled "Sun'in mankō" (寸陰蔓稿), depicting popular scenes of Japan. The following year, she created another series of pictures, showcasing her versatility and commitment to capturing Japanese culture through her art.

Yūkō's personal life was closely intertwined with her professional journey. She married Watanabe Bunzaburō (渡辺 文三郎, 1853–1936), a fellow painter who had also studied under her father. This union further solidified her connections within the art community and provided mutual support in their artistic endeavors.

Beyond her artistic achievements, Yūkō was dedicated to the advancement of women's education in Japan. She taught at the Gakushūin Women's Higher School (学習院女子高等科), an institution established to educate women of the nobility. Her role as an educator reflected her commitment to empowering women through education, aligning with the broader societal shifts of the Meiji era that sought to modernize and elevate the status of women.

Watanabe Yūkō's life and work exemplify the challenges and triumphs of female artists in Meiji Japan. Her ability to navigate the male-dominated art world, coupled with her dedication to education, underscores her significant contributions to Japanese art and society.

Two Signatures, One Artist: A Closer Look at Watanabe Yūkō’s Types Japonais (1886)

While examining copies of Types Japonais (1886), we came across a fascinating variation in one of Watanabe Yūkō’s plates—her illustration of a woman playing the zhongruan (中阮, chūgen), a traditional Chinese plucked string instrument from the lute family.

This particular image appears with two different versions of her signature. In one, “Y. WATANABE” is printed in a mechanical, typeset-like style—but with a peculiar flaw: the “N” is reversed, as if mistakenly transferred from a printing plate. In the other version, her name appears in a more natural, handwritten style, with the lettering corrected.

We believe Watanabe herself may have noticed the error and had it corrected in a subsequent edition. The illustration remains unchanged, but this subtle revision reveals a rare glimpse into the production process and the artist’s attention to detail.

Such minor differences can offer important clues about the printing history of Meiji-era illustrated works, especially those made for export or Western audiences.

Wednesday, April 2, 2025

山下久馬太 Yamashita Kumata Rare Meiji Japanese Artist

Yamashita Kumata (山下久馬太), a rare and lesser-known artist of the Meiji Period, graduated from the Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts in July 1886 (Meiji 19). This institution, established during a transformative era in Japanese history, was instrumental in shaping modern Japanese art by blending traditional techniques with Western influences. At a time when Japan was rapidly modernizing, the school aimed to cultivate a new generation of artists who could navigate the convergence of Eastern and Western artistic traditions. Yamashita, like many of his peers, was trained in both Eastern and Western painting styles, equipping him with the technical skills and conceptual understanding to contribute to Japan’s evolving art scene.

The Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts was part of a broader effort to preserve Japan’s cultural heritage while embracing Western artistic methods. Graduates from its Tōsō and Sōsō art departments were known for their dual expertise, a hallmark of Meiji-era artists. Yamashita’s education at this institution would have provided him with a strong foundation to engage with the dynamic artistic landscape of his time.

Two postal cards sent by Yamashita offer a glimpse into his life and work. The first, postmarked January 2, 1890, lists his return address as Kyoto Jinjō Shihan Gakkō (京都尋常師範学校), or Kyoto Normal School, a teacher training institution established in 1876 (Meiji 9) to address the need for qualified educators during Japan’s educational reforms. The second card, dated June 15, 1891, shows his address in Kyoto’s Kamikyō Ward (京都市上京区). Both cards bear the postmark “Yamashiro Kyoto” (山城京都). The 1891 card is addressed to Maeda Yoshihiko, identified as an oil painter (油画師, Aburaeshi), and appears to be a letter of inquiry related to art, specifically concerning the use and significance of colors.

NOTE: The third postcard displayed here, labeled as "sample," is included from a separate listing. It serves as evidence to demonstrate the connection between Yamashita Kumata (山下久馬太) and Hikita Keizō (疋田敬蔵), illustrating that the two were acquainted with each other.

The sole reference to Yamashita Kumata’s identity as an artist is a painting he created in 1887, titled 臥竜松真写: 臥竜松在于備前和気郡大内村一ノ井氏庭中 (True Depiction of the Garyū Pine: The Garyū Pine Located in the Garden of the Ichii Family in Ōuchi Village, Wake District, Bizen). Yamashita’s role in the artistic circles of the Meiji era is further highlighted by his close association with Hikita Keizō (疋田敬蔵), a Western-style painter and educator who studied under Antonio Fontanesi at the Kobu Bijutsu Gakko, as evidenced by our postal card dated May 22, 1891, from Yamashiro, Kyoto, which bears both of their names as senders.

This card not only confirms their acquaintance but also suggests a collaborative relationship, possibly extending to Maeda Yoshihiko, reflecting their shared artistic spirit. Additionally, Yamashita’s influence is underscored by his work as a drawing instructor for Kojima Torajirō (児島虎次郎, 1881–1929), further cementing his place within the creative networks of the time.