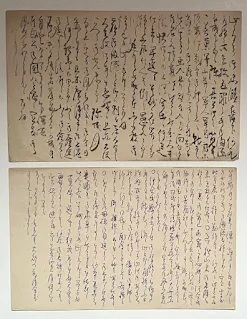

These two postcards (above) were sent by 長谷川栄次郎 (Hasegawa Eijirō) from Futami, Harima (now part of Hyōgo Prefecture), with postmarks dated September 1 and September 15, 1891. Despite our efforts, we’ve been unable to uncover any details about Hasegawa Eijirō. Interestingly, we also have another postcard sent from Futami, Harima, (see below) dated June 29, 1891. While the sender’s name is illegible...could be 木村常治 ? ...the message includes a reference to Hasegawa Eijirō, suggesting a connection between the two. It’s clear that something significant was happening between these individuals, as they both sent cards to Maeda Yoshihiko. Unfortunately, the exact reason for their correspondence remains a mystery.

Maeda Yoshihiko (前田吉彦, 1849–1904), also known by his artistic name Gizen (蟻禅), was a Japanese Western-style painter of the Meiji period, though he remains largely unknown outside Japan. This blog presents previously unpublished insights into his life and work through correspondence from historical figures and fellow artists of the time, offering a unique glimpse into his personal connections and the cultural context of the era.

Friday, January 31, 2025

Who was Hasegawa Eijirō of Futami Hyōgo?

Wednesday, January 29, 2025

水口龍之助 (Mizuguchi Ryūnosuke) 森琴石 (Mori Kinseki)

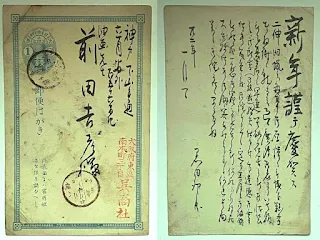

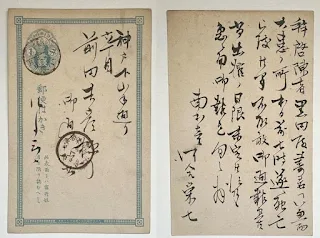

When we published the post titled "1889 Lithograph and Copperplate Engraving Society of Osaka Meeting Notice" on December 7, 2024, we were unable to decipher Mizuguchi's first name from the postal card featured in that article. However, we have since discovered another card written by him, where his full name is clearly legible. This card, dated December 31, 1888, was addressed to Maeda Yoshihiko. It is a simple New Year’s greeting card, featuring Mizuguchi’s return address: 3 Chome Nakamachi, Osaka.

It is worth noting that, although our progress has been slower than we had hoped, previously unknown historical accounts of the Meiji art world are gradually coming together, much like a jigsaw puzzle. Pieces that once seemed disconnected or nonsensical are now fitting into place, forming a clearer picture over time.

When we first embarked on this project, we had little idea where it would lead. Our initial lack of knowledge about the Meiji period—its art, people, and related philatelic materials—presented a significant challenge. However, as the project unfolds and the pieces start to align, we find ourselves overcoming these obstacles.

Now, we can vividly imagine how vibrant life was during that era. We see the Meiji period in living color, with real people who thought, lived, and wrote in ways we are beginning to understand more deeply.

Mizoguchi Ryūnosuke - Mori Kinseki - and Copperplate Art

Copperplate engraving may not be the first technique that comes to mind when thinking about traditional Japanese art, but it played a significant role in Japan's printmaking history, especially during the late Edo and early Meiji periods. In Osaka, 水口龍之介 (Mizoguchi Ryūnosuke) was one of the key figures in the development of this craft. His work in copperplate engraving, particularly his involvement in creating official seals and his contributions to the engraving community, helped establish Osaka as a hub for this intricate art form.

By the late Edo period, Japan was being exposed to Western influences, and techniques such as copperplate engraving were introduced. This method allowed for highly detailed, precise prints, which were ideal for producing government documents, official seals, and academic works. As the country began to modernize, cities like Osaka, alongside Kyoto, became centers for refining these techniques. Mizoguchi, trained under the esteemed 玄々堂 (Gen-Gendo) school, quickly gained a reputation for his technical skill and precision. His early works in engraving 官札 (official certificates), which were used for authentication by the government, showcased his ability to handle complex and intricate designs with remarkable accuracy.

Mizoguchi’s contributions to the Osaka engraving scene went beyond his personal work. After gaining experience, he returned to Osaka, where he became instrumental in the establishment of the 銅版組合 (copperplate engraving guild), a professional network for engravers. This guild helped standardize techniques and establish best practices, raising the profile of copperplate engraving in the region. Mizoguchi’s leadership within this guild played a crucial role in developing Osaka into one of Japan's most important centers for copperplate printing.

Mizoguchi’s influence extended through collaborations with other prominent figures in Osaka’s engraving community. One such figure was 森琴石 (Mori Kinseki), a well-respected engraver who, like Mizoguchi, contributed significantly to the craft. Mori, originally from 摂津州有馬 (Settsu Province), had trained in Western-style painting before turning to copperplate engraving. Under his studio name 響泉堂 (Kyōsendō), he created some of the most technically advanced copperplate works of the Meiji period, including collaborations with Mizoguchi.

One of their most notable joint works was the 達爾頓氏生理学書図式 (Dalton’s Physiology Illustrations), published in 1878, which helped expand the reach of copperplate engraving for academic purposes. In addition, Mori produced some of the finest works in the field, including a copperplate series of illustrations based on the 康煕 (Kangxi) edition of Chinese works, showcasing the high level of craftsmanship achievable through the technique. These works remain some of the finest examples of copperplate engraving from the Meiji era, demonstrating not only technical proficiency but also an understanding of fine artistic composition.

Monday, January 27, 2025

片野正栄館 洋画師 Western-Style Painter 1890

We have four postcards here, all sent from Osaka on the following dates: January 4, 1888; February 18, 1888; January 4, 1890; and February 10, 1890. The sender is 片野正栄館 (Katano Shoeikan), a publisher based in Osaka, whose address is listed as 大坂東区 (Higashiku, Osaka). Katano was known for publishing educational textbooks on art and patriotic themes during the 1870s to 1890s. While the two "New Greetings" cards follow the typical format of polite correspondence, the other two appear to address more serious matters.

The texts seem to address administrative matters, focusing on the established regulations and the importance of adhering to authority as defined by the law. It maintains a formal and instructional tone throughout, emphasizing the necessity of strict compliance with rules, unity among officials, and the ethical standards expected of samurai and other public servants. Additionally, it highlights the role of officials in upholding the integrity of the law and maintaining order within their duties.

Although quite interesting, such subject matter is well beyond the scope of our blog.

Two of the postcards refer to Maeda Yoshihiko as 油画師 (aburaeshi), or oil painting artist, a title we’ve frequently encountered in this postcard collection. However, the card dated February 10, 1890, addresses him as 洋画師 (yōgashi), or Western-style painter. This marks the first time we’ve come across this specific title. From these titles, we can now confidently conclude that Maeda was recognized as a Western-style oil painter.

Saturday, January 25, 2025

前田農夫 (Maeda Atsuo) Relative of Maeda Yoshihiko (前田吉彦)

We have an intriguing set of three postcards here, all postmarked in Osaka in 1886, dated January 8, January 19, and July 31. The sender lists his return address as 大坂府土佐堀通り (Tosabori-Douri, Osaka).

The first postcard (see photo 1 above) provides our initial clue. The sender writes his name as 召の茄太郎, using the hiragana "の" (no) in place of the second character of his name. Based on this, we initially read the name as "Shouno Katarou."

The second postcard (see photo 2 above) offers a more standard version of his name: 召野茄太郎, where "野" replaces the hiragana "の." However, this card also includes a red ink stamp beneath his name. Unfortunately, the stamp is partially obscured by overlapping ink, making the characters difficult to decipher (see photo 3 below).

The third postcard (see photo 4 below) adds a surprising twist. Here, the sender writes his name as 間野茄太郎 (Mano Katarou). This variation sheds light on the mystery of the red stamp—the first character might indeed be "間" (ma). It also suggests that "召," used on the first card, could have been a simplified or shorthand version of "間."

These variations create a fascinating puzzle, one that offers us glimpses into how names were written and adapted at the time. While some questions remain unanswered, they provide an engaging challenge, allowing us to piece together fragments of history in the process.

The card dated July 31 (see photo 2) is addressed to three individuals: Maeda Yoshihiko (前田吉彦), Maeda Atsuo (前田農夫), and Udagawa Kingo (宇田川謹吾). In our post from November 16, 2024, we showcased another card with Udagawa Kingo (宇田川謹吾) as the recipient. While his identity remains unknown, the fact that he stayed at the Maeda residence on another occasion suggests he was likely someone close to the family.

Now we arrive at the intriguing question: who was Maeda Atsuo? Could he have been a relative of Maeda Yoshihiko? While Maeda is a common surname, the presence of another Maeda in the same household may not simply be a coincidence.

In the 大蔵省職員録 (Ministry of Finance Staff Directory, March 1877), Maeda Atsuo is listed as 士族岡山縣前田農夫 (Samurai from Okayama Prefecture). This detail is significant, as Maeda Yoshihiko was also from Okayama and of samurai heritage. These shared origins strongly suggest a familial connection between the two.

Furthermore, there is evidence linking Atsuo to the city of Kobe, where Yoshihiko taught art classes. Maeda Atsuo is mentioned in the 神戸権勢史 (History of Kobe's Influential Figures), further tying him to the same circles and locations as Yoshihiko. This overlapping context of geography, class, and activity strengthens the likelihood that their relationship was more than coincidental.

Friday, January 24, 2025

河合新蔵の父、河合栄七からのはがき

I searched extensively for information on the family members of Kawai Shinzo, but such details seem to be nearly nonexistent, apart from brief mentions of his wife and two daughters. However, we believe this Kawai Eishichi (河合栄七) is Shinzo's father, based on the return address, Minami-honmachi, Osaka (大阪 南本町), which Shinzo frequently used. According to the National Diet Library Search, Eishichi is noted as having invested money in a business venture.

This postcard is postmarked August 3, 1889, in Settsu, Osaka. In it, Eishichi appears to consult Maeda about a matter involving Mr. Kuroda—most likely Kuroda Uhei (黒田夘兵衛) of Kure Shosha in Osaka (大坂呉商社), referenced in our post dated January 18, 2025. Eishichi describes the situation as challenging and emphasizes the need for careful deliberation. He also seeks Maeda’s insight, asking for his thoughts and guidance at the earliest opportunity.

While the exact subject matter remains unclear, it likely pertains to a business connected to art supplies, a field we believe Kuroda was involved in.

Wednesday, January 22, 2025

丸裁巻刀 Honsou (本惣) Maker Shibata Kita of Osaka 1886

Postmarked on August 11, 1886, in Osaka, this postcard provides a fascinating glimpse into the world of Meiji-era craftsmanship. The sender, Shibata Kita, was a specialist in precision cutting tools and operated out of Osaka Honmachi 1-chome, as indicated by the red return address stamp. Within the rectangular stamp is a small oval mark (本惠) that signifies his expertise in crafting “Marusai Bocho” (丸裁巻刀), a specialized blade designed for cutting washi, the Japanese rice paper used in woodblock printing and other artistic applications. These blades were also indispensable for cutting shoji paper, cloth, and other materials requiring precise cuts.

This letter is likely a follow-up on an order Maeda placed for a Marusai Bocho. The phrasing, especially '如何相成候哉' (how is it working out for you?) and '早速にても御返事被下度候' (I would appreciate your reply as soon as possible), strongly suggests that Shibata Kita is seeking feedback regarding the order.

Monday, January 20, 2025

鈴木重持 Suzuki Shigemochi School Teacher

Postmarked December 31, 1888, and January 3, 1889, in Kumamoto, these New Year’s cards were sent by Suzuki Shigemochi (鈴木重持), an educator who was likely once a student of Maeda. Why did Suzuki send two cards just days apart? He may have forgotten he had already sent one or was unsure if it had been mailed. Either way, the second card was likely sent out of caution or courtesy.

Saturday, January 18, 2025

黒田夘兵衛 大坂呉商社 油画師

Friday, January 17, 2025

Honda Sada (本田貞) of Mihara, Bingo Province 1891

This postcard, postmarked December 1, 1891, stands out as the only one among over 300 cards addressed to Maeda Yoshihiko from Bingo Province (now part of Hiroshima Prefecture). This rarity suggests that the sender, Honda Sada, was either not closely acquainted with Maeda or was visiting Bingo from another region. It is also possible that Honda corresponded with Maeda from other locations, but we have yet to uncover additional postcards from him in this collection.

The sender's partial return address reads 備後国xxx郡三原町大字大xxx, though some portions remain unclear. Honda signed his name as 本田貞, but it is possible that he omitted an additional character for reasons unknown. Despite our efforts, we were unable to locate any online records or references to him, leaving his identity and background a mystery.

Wednesday, January 15, 2025

備中高梁の油画師 Maeda Yoshihiko

These three cards are dated January 4, 1889; January 2, 1890; and May 30, 1890. All bear postmarks from Takahashi, Bitchu. The card dated January 2 was sent by 村井依継 (Murai Yoritsugu, government employee of Bitchu, Oda-ken, likely a former samurai). The May 30 card was sent by Adachi Toshitsune and addresses Maeda Yoshihiko as 油絵師 (abura-e-shi), while the January 4 card refers to him as 油画師 (abura-e-shi). The sender of the January 4 card is partially identified as 召xx郎.

So, what is the difference between 油画師 (abura-e-shi) and 油絵師 (abura-e-shi)? Both share the same reading and meaning but are written with different kanji. During the Meiji period, 油画師 was likely more commonly used in formal or academic contexts. Here's why:

The term 油画 (oil painting) was introduced alongside the Western painting tradition (洋画) during the Meiji period, as Japan rapidly adopted and adapted Western art styles. The kanji 画, seen in terms like 洋画 and 日本画, was associated with fine art and often appeared in formal settings such as academic discussions, exhibitions, and art institutions.

In contrast, while 油絵師 would have been understood, the kanji 絵 carried a slightly less formal connotation. It was traditionally tied to Japanese art forms like 絵巻 (picture scrolls) and 浮世絵 (woodblock prints). This term might not have been as widely used to describe artists working in the Western oil painting style during that time.

A Meiji-period individual would most likely use 油画師 in contexts related to Western art education, formal writings, or professional titles. 油絵師 may have been used more casually or gained popularity later as oil painting became more integrated into Japanese artistic practices.

Monday, January 13, 2025

Gojo Nara - Kuriyama to 油絵師 前田吉彦

The Kuriyama Family Residence, located in Gojo City, is Japan’s oldest private home with a confirmed construction date. It’s not just an old building—it’s a link to the lives of Edo-period merchants. Two fascinating greeting cards, mailed from Nara, Yamato by Kuriyama (栗山) of Gojo (五条) in 1889 and 1890, offer a personal glimpse into this family’s story. The 1889 card, addressed to Maeda Yoshihiko and referring to him as "aburaeshi" (油絵師, oil paint artist), hints at the connections and prominence of the Kuriyama family. Although Kuriyama’s first name is illegible, he was undoubtedly one of the wealthy Kuriyamas, prominent merchants of Nara.

The Kuriyama family were key players in Gojo’s growth as a trade hub, bridging the gap between rural producers and urban markets. Their influence extended beyond commerce, as evidenced by their connections reflected in these postcards. These cards offer a rare glimpse into the social networks and relationships of a prominent merchant family from over a century ago.

Saturday, January 11, 2025

六要画 油絵師 前田吉彦 明治22年

These two postcards present a real mystery. The one on the right, postmarked January 7, 1890, from Tokuyama, Suō (周防徳山) — now part of Yamaguchi Prefecture — has a return address of Tsuno-gun, Suō, Yamaguchi Prefecture (山口県周防国都濃郡). It was sent by someone named Miyoshi Miyo (三吉ミヨ), a name that sounds like it could belong to a woman, though determining gender from names alone can be tricky. The postcard addresses Maeda Yoshihiko as 油絵師 (aburaeshi, "oil painter"), which appears to have been a common practice, as there are quite a number of similar postcards in our collection.

After searching combinations of terms such as "Miyoshi," "Tokuyama," "Yamaguchi," "Meiji," and "Artist," I found an artist named Ōba Gakusen (大庭学僊), born in Tokuyama in 1820, whose birth name was Miyoshi Yuriyoshi (三吉百合吉). While it's unclear how "Miyoshi Miyo" might be related to this artist, it's not uncommon for artists of that era to use multiple names. It's possible that our "Miyoshi Miyo" is, in fact, Miyoshi Yuriyoshi.

The postcard on the left was postmarked January 3, 1889, from Sumoto, Awaji (淡路洲本), now part of Hyogo Prefecture. The sender's name and address are illegible. The postcard addresses Maeda as 六要画 前田吉彦 (Rokuyōga Maeda Yoshihiko), suggesting that Maeda Yoshihiko was recognized as an artist whose work reflected the principles of the Six Essentials of Painting (六要画). The sender may have used this term to emphasize Maeda's connection to classical artistic ideals, even though he was known for his Western-style painting. It could imply that Maeda's works were viewed as embodying the spirit of these traditional principles in some way.

Thursday, January 9, 2025

Yokochi Ishitārō - Distinguished Educator and Archaeologist 1890

This New Year's greeting card was sent by Yokochi Ishitārō (横地石太郎) to Maeda Yoshihiko. It is postmarked in Kagoshima, Satsuma (薩摩鹿児島), and dated January 4, 1890. Yokochi's return address is listed as Kagoshima Junior High School (鹿児島高等中学造士館).

Yokochi Ishitārō (1860 – 1944) was a Japanese educator and archaeologist. Born in Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture, into a samurai family, he later became a prominent figure in Japan's educational and academic circles. After graduating from the University of Tokyo with a degree in applied chemistry, Yokochi worked as a teacher and principal at various schools across Japan, including in Kobe, Kyoto, and Kagoshima. He was appointed as the principal of several schools in Fukushima and Ehime Prefectures, contributing to educational reforms. Ultimately, he became the head of Yamaguchi Higher Commercial School, where he continued his work until his retirement in 1924.

Although Yokochi’s academic background was in physical chemistry, he had a wide-ranging interest in other fields, particularly archaeology, astronomy, and geology. His contributions to archaeology were especially significant in Ehime Prefecture, where he conducted excavations and published several academic papers. His interest in archaeology extended beyond his professional work; he was deeply involved in the preservation of cultural heritage and conducted research on ancient burial mounds and artifacts, publishing his findings in various academic journals.

Hisada Michi 久田道 Echigo Niigata

The two postcards featured here are customary New Year’s greetings, postmarked January 2, 1889, and January 1, 1890, from Echigo Niigata (越後新潟). The sender, identified as Hisada Michi, provided a return address listed as Niigata-shi (新潟市), though his full address remains indecipherable. Despite this small glimpse into his identity, there is no additional correspondence from Michi to Maeda Yoshihiko, suggesting their connection may have been distant, marked only by the tradition of exchanging New Year’s greetings.

Customary in Japan, New Year postcards are a way to convey good wishes and maintain social ties, even among acquaintances. The lack of further correspondence hints that Michi and Maeda’s relationship might not have extended beyond formal gestures of courtesy. Unfortunately, efforts to uncover more about Hisada Michi have yielded no further insights, leaving him a fleeting figure in the historical narrative tied only to these thoughtful, ephemeral greetings.

Monday, January 6, 2025

Kikui Kamejiro 菊井亀次郎 Bizen Oil Paint Artist 油絵氏 Kobe

These two postcards, postmarked in Bizen on January 4, 1890, and July 30, 1891, were sent by Kikui Kamejiro (菊井亀次郎), who provided his return address as Taiji, Iwabuson, Iwanashi-gun, Bizen (備前磐梨郡石生村大字). Notably, Kikui addressed the recipient, Maeda Yoshihiko, as "oil paint artist" (Abura-Eshi, 油絵氏). This title appears frequently on other postcards sent to Maeda around 1890, indicating his established reputation as a skilled practitioner of oil painting. Such consistent recognition underscores Maeda’s prominence in the artistic circles of the time. Unfortunately, as is often the case with many other postal cards in this collection, we have been unable to uncover who Kikui Kamejiro was in a historical context.

Saturday, January 4, 2025

Who Was Kobori Kazunosuke (小堀数之助) of Takahashi, Bitchu?

Wednesday, January 1, 2025

Newly Discovered Ink Drawing Dated 1890 by Kawai Shinzo

This photo and post were first shared on September 15, 2024, when we knew almost nothing about these postcards or how to interpret their contents. Since then, we’ve been piecing together the story, one fragment at a time. Progress has been slow—like assembling a 1,000-piece puzzle with only a few pieces in place. With continued effort and a little luck, we hope to uncover more. For now, we’re pleased to share that we’ve identified the sender of this postcard.

*From our review of the available correspondence, it appears that Kawai Shinzo preferred using the name 河合新造 rather than 河合新蔵, at least prior to his emergence as a prominent artist.

*This 1926 woodblock print by Yoshida Hiroshi (1876-1950) shows Kawai Shinzo's two daughters.

This postal card bears the postmark of Osaka, dated January 1, 1890. It was sent from Minami-Honmachi, Osaka (大阪 南本町1丁目) by Kawai Shinzo (河合新蔵, 1867–1936) prior to his rise to prominence as a Western-style painter, while he was still studying under the guidance of Maeda Yoshihiko (前田吉彦) in Kobe.

There are many watercolor paintings by Kawai, with the majority featuring landscapes, making his works relatively accessible. However, we have not been able to locate any of his ink drawings online or find references to such works. As we are merely scratching the surface of Japanese art—a field in which our knowledge is very limited—our observations should be taken as preliminary. Our aim is simply to share previously unpublished material and provide readers with insights using the resources available to us.

Kawai Shinzō (1867–1936) was a distinguished Japanese painter whose career spanned a transformative era in Japanese art history. Born in Osaka, he demonstrated an early aptitude for painting and studied under Maeda Yoshihiko, a respected figure in Western-style art who taught pencil drawing at the Kobe School. Under Maeda’s tutelage, Kawai developed his skills in Western-style techniques, which influenced his artistic approach.

In 1891, Kawai moved to Tokyo, where he joined the Goseda school, a prominent art school for Western-style painting. This decision would prove pivotal to his artistic development. At the time, Tokyo was a vibrant hub of cultural and artistic innovation, attracting some of the most talented and ambitious artists in Japan. The city provided Kawai with access to new ideas, techniques, and artistic movements, including the growing influence of Western art. This exposure allowed him to expand his creative repertoire, blending traditional Japanese aesthetics with elements of Yōga (Western-style painting).

Throughout his career, Kawai's works often depicted natural landscapes, showcasing his exceptional skill in watercolor. He used the medium to capture subtle nuances of light and atmosphere, exemplifying his ability to blend Western techniques with Japanese sensibilities into harmonious and evocative compositions.

Below is what was published on September 15, 2024.

前田吉彦 神戸美術先生 1890年のオリジナルアート付き年賀状

この1890年の年賀状(明治23年1月1日)は、大阪から作者不明のアーティストによって送られました。作品には、凛々しい馬に乗って微笑む男が描かれており、彼は日の出の旗を掲げ、背景には城が見えます。描画のシンプルさがそのインパクトを高めています。1890年が午年であったため、この作品に描かれた勇ましい馬には象徴的な意味が込められているのでしょう。

よく見ると、男の服にいくつかの文字があり、城のすぐ下にはアーティストのサインらしきものがあります。これらの文字ははっきりとはしていません。その為、この芸術的なはがきの送信者は不明です。どなたかこの送信者を特定できる読者がいるかもしれません。

New Year's Card from 1890 with Original Artwork Addressed to Maeda Yoshihiko, Western-Style Painter

This New Year's card from 1890 (Meiji 23, January 1st) was sent from Osaka by an unknown artist. The artwork depicts a smiling man riding a gallant horse, holding a rising sun flag, with a castle visible in the background. The simplicity of the drawing enhances its impact. Since 1890 was the Year of the Horse, the brave horse depicted in the artwork likely holds symbolic meaning.

Upon closer inspection, there are some characters on the man's clothing, and what appears to be the artist's signature just below the castle. However, these characters are not clear, making it difficult to identify the sender of this artistic postcard. Perhaps a reader might be able to identify the sender.

.jpg)