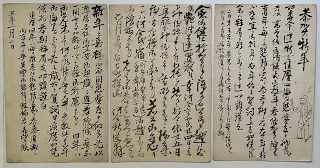

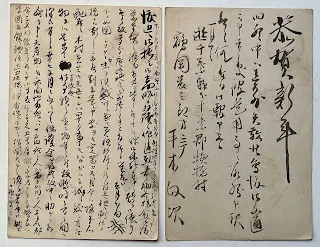

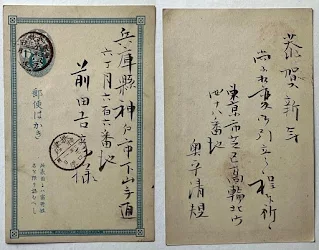

These five cards are postmarked January 23, 1889; April 6, 1889; August 15, 1889; January 1, 1890; and May 2, 1890. Four were sent from Shimoya, Tokyo, and one from Shimōsa, Kemigawa (検見川下総), in what is now Chiba Prefecture.

Hiraki Masatsugu: A Pivotal Figure in the Evolution of Western-Style Painting in Japan

Hiraki Masatsugu (平木政次, 1859–1943) was a renowned Western-style painter who navigated the complexities of Japan's transition from the Edo period to the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa periods. His artistic career spanned several decades, and his contributions to the development of Western-style painting in Japan are considered significant. He was born in 1859, in the Edo residence of the Bitchu Matsuyama Domain, present-day Okayama Prefecture. His early life as the eldest son of Hiraki Masanori, a samurai of the Bitchu Matsuyama Domain, placed him within a traditional Japanese context that was gradually giving way to Western influences as the country began its modernization in the late 19th century.

Early Education and Mentorship

In 1873, at the age of 14, Hiraki moved to Yokohama, a city that was becoming a focal point for international trade and the influx of Western ideas following Japan's opening to the outside world in the 1850s. This relocation marked the beginning of Hiraki's exposure to Western-style painting, a domain that was increasingly gaining popularity among Japanese intellectuals and artists. It was here that he began studying under the prominent painter Goseda Horyu (五姓田芳柳, 1827–1892), a well-regarded figure in the Yokohama art community. Goseda, who had studied under Western-trained artists, was influential in introducing Hiraki to the techniques and methods of Western-style painting. In 1873, the two relocated to Asakusa, a district in Tokyo that was emerging as a hub for artistic and intellectual exchange during the early Meiji period.

This formative period under Goseda's tutelage played a critical role in Hiraki’s artistic development. As he absorbed Western techniques in painting, Hiraki's works began to reflect the blend of Japanese tradition and Western influence, which was a central theme in the works of many Meiji-era artists.

Relocation to Osaka and Lithography

By 1878, Hiraki followed his teacher to Osaka, where he expanded his artistic horizons. It was in Osaka that he became acquainted with Maeda Yoshihiko, a figure who would later play an important role in his artistic development. In the same year, Hiraki joined Matsuda Ryokuzan’s Gengendo studio, where he delved into the techniques of lithography, an important medium that facilitated the dissemination of art and ideas during this period of modernization. Lithography provided Hiraki with a new avenue for artistic expression, allowing him to produce works that were accessible to a broader audience, which was crucial in an era where Western ideas were rapidly permeating the social and cultural fabric of Japan.

Career at the Education Museum

By 1880, Hiraki had secured a position as an artist at the Education Museum (now known as the National Museum of Nature and Science). In this role, Hiraki was tasked with drawing accurate representations of plants, animals, and other specimens, which were intended to support the burgeoning scientific community in Japan. His time at the Education Museum allowed him to hone his skills in realistic rendering, and these experiences would later influence his Western-style works, as he increasingly sought to capture the natural world with the precision and techniques of European academic painting.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Hiraki’s early works began to gain attention at national exhibitions. His painting "View of Mount Fuji from Kudan Shokonsha Shrine" was exhibited at the First Domestic Industrial Exposition in 1877, and his painting "By the Banks of Shinobazu Pond" was showcased at the Second Domestic Industrial Exposition in 1881. These exhibitions were crucial for promoting Western-style art in Japan, and Hiraki’s participation marked him as one of the key figures in the early movement toward adopting and adapting Western artistic practices.

In 1889, Hiraki joined the Meiji Art Association (明治美術会), an important group of artists committed to Western-style painting, and later became a technical assistant at the Faculty of Science at the Imperial University of Tokyo. His work was frequently displayed at major exhibitions, and his reputation as a leading artist continued to grow.

Contribution to the Bunten Exhibition

Hiraki’s artistic journey reached a significant milestone when he participated in the first Bunten Exhibition in 1907, an event that was part of the government's efforts to foster a modern national identity through art. His submission, titled "Remaining Snow," was well-received and further cemented his standing within the art community. The Bunten, which became a major annual event, provided a platform for artists to showcase their work while adhering to state-sponsored ideals of art, which combined elements of Western techniques with Japanese subject matter.

Later Years and Legacy

As the 20th century progressed, Hiraki’s reflections on the evolution of Western-style painting in Japan became increasingly significant. In 1936, he published "Retrospective of the Western Painting World in the Early Meiji Era" (明治初期西洋画界回顧), a detailed account of his experiences and observations of the dramatic shifts in the Japanese art scene during the Meiji period. The work, serialized in the magazine Ecchingu, provided a chronological narrative of the formative years of Western-style painting in Japan, offering an insider's view of the early artistic transformations that reshaped the nation's visual culture. This publication not only contributed to the historical documentation of the period but also highlighted Hiraki’s own central role in bridging the traditional with the modern.

Hiraki Masatsugu’s career was not merely a personal journey of artistic development; it was also a reflection of the larger cultural and political changes occurring in Japan during a time of intense transformation. His works represent the intersection of Japanese tradition and Western influence, and his ability to adapt Western techniques to Japanese subjects helped lay the groundwork for the future of modern Japanese painting.

Hiraki passed away in 1943 at the age of 85, leaving behind a substantial legacy that continued to influence future generations of artists. His life and work remain a testament to the ways in which art can both reflect and shape the broader historical currents of a nation. Through his paintings and writings, Hiraki helped document a pivotal era in Japanese art history, one that saw the introduction of Western artistic practices and their integration into the traditional Japanese artistic canon.

In conclusion, Hiraki Masatsugu's contributions to Western-style painting in Japan are invaluable, not only for their artistic merit but also for their historical significance. His career encapsulates the Meiji era’s artistic revolution, a period when Japan actively sought to modernize by embracing and adapting Western ideas while maintaining its unique cultural identity. Through his participation in exhibitions, his role as a teacher and mentor, and his reflective writings, Hiraki played an essential role in shaping the trajectory of Japanese art during a crucial period of cultural exchange and transformation.